FreeSimpleGUI

User Interfaces for Humans - Transforms tkinter, Qt, Remi, WxPython into portable people-friendly Pythonic interfaces

The Call Reference Section Moved to here

This manual is under construction as we adapt changes to FreeSimpleGUI and make simplifications. Some links may not work as expected. References to "PySimpleGUI" can safely be assumed to be interchangable with "FreeSimpleGUI"

Jump-Start

Install

pip install FreeSimpleGUI

or

pip3 install FreeSimpleGUI

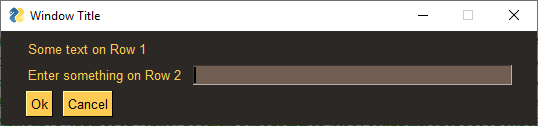

This Code

import FreeSimpleGUI as sg

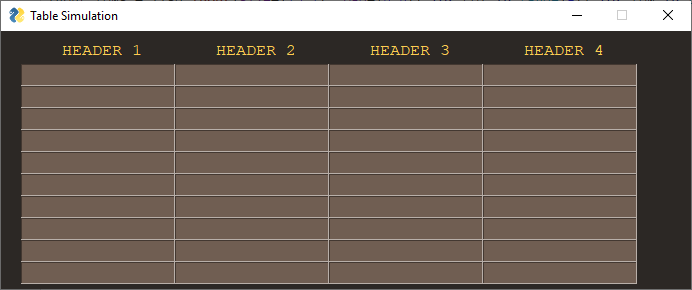

sg.theme('DarkAmber') # Add a touch of color

# All the stuff inside your window.

layout = [ [sg.Text('Some text on Row 1')],

[sg.Text('Enter something on Row 2'), sg.InputText()],

[sg.Button('Ok'), sg.Button('Cancel')] ]

# Create the Window

window = sg.Window('Window Title', layout)

# Event Loop to process "events" and get the "values" of the inputs

while True:

event, values = window.read()

if event == sg.WIN_CLOSED or event == 'Cancel': # if user closes window or clicks cancel

break

print('You entered ', values[0])

window.close()

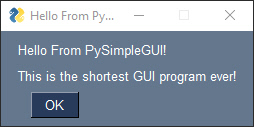

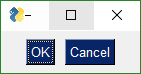

Makes This Window

and returns the value input as well as the button clicked.

Background - Why FreeSimpleGUI Came to Be

Once upon a time there was a package called PySimpleGUI that people liked a lot. The owners decided to rug-pull its

continued availability and re-license it with a proprietary commercial license under a paid subscription. FreeSimpleGUI

is the continuation of the LGPL3 licensed version last available.

FreeSimpleGUI will remain free and permissively licensed forever.

What's newer?

New APIs to save you time - not just for beginners

- Exec APIs (execution of subprocesses)

- User Settings APIs (management of settings in form of a dictionary)

- Threading API call -

write_event_value - True multiple windows support -

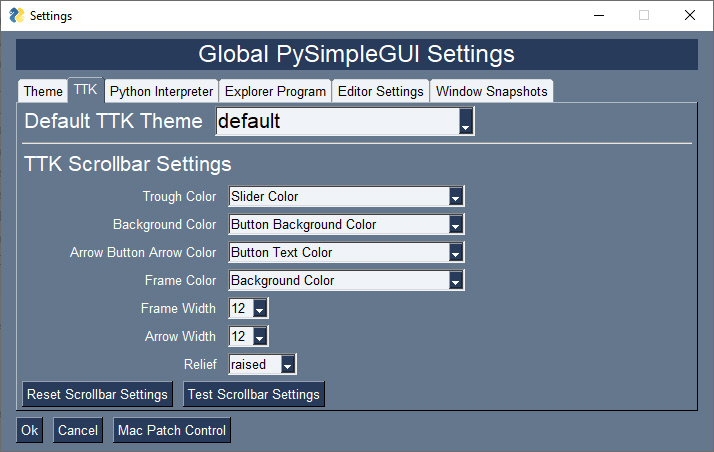

read_all_windows - System-wide global settings - theme, interpreter to use, Mac settings, ...

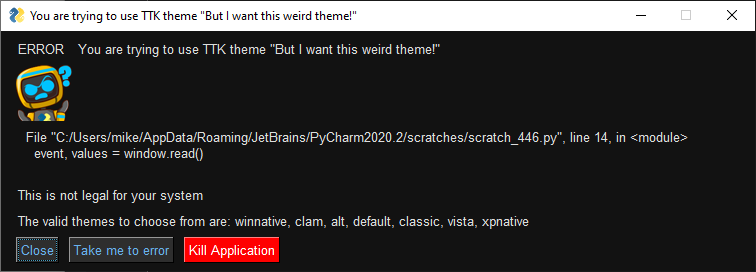

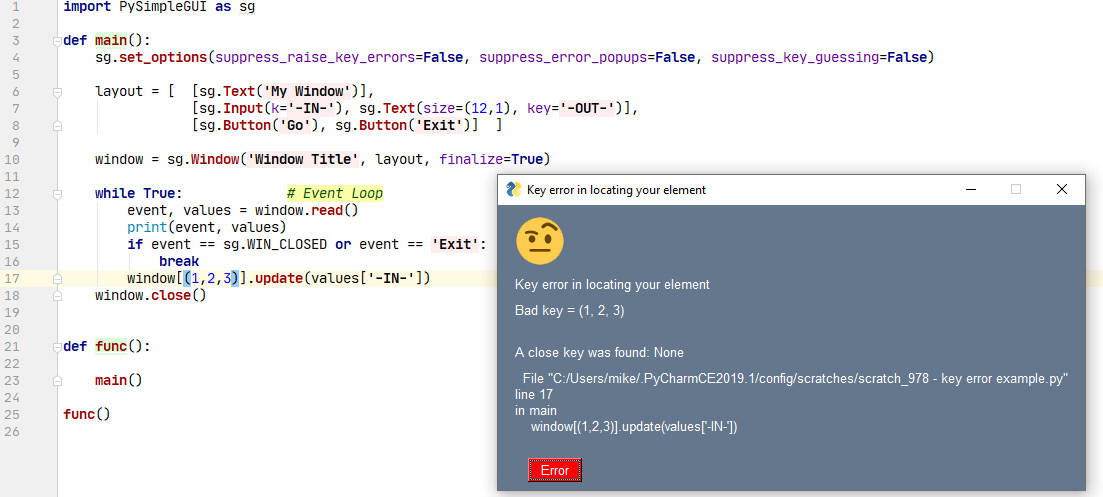

- Advanced error handling including launching your editor to line of code with error

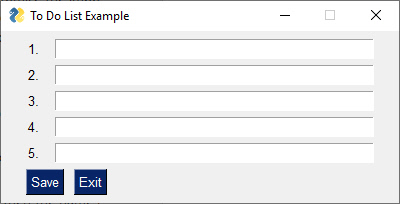

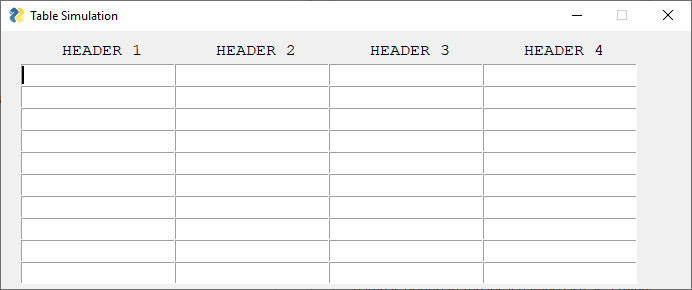

- More advanced layouts - still trivial,maybe more trivial, to make windows

- Go wild - have a complicated (i.e. not simple) application... no problem here supporting your App. "It's on you". PSG solved the GUI problem, but you still have to make an application

- Docstrings - Tight integration with docstrings provides type checking and in-IDE documentation

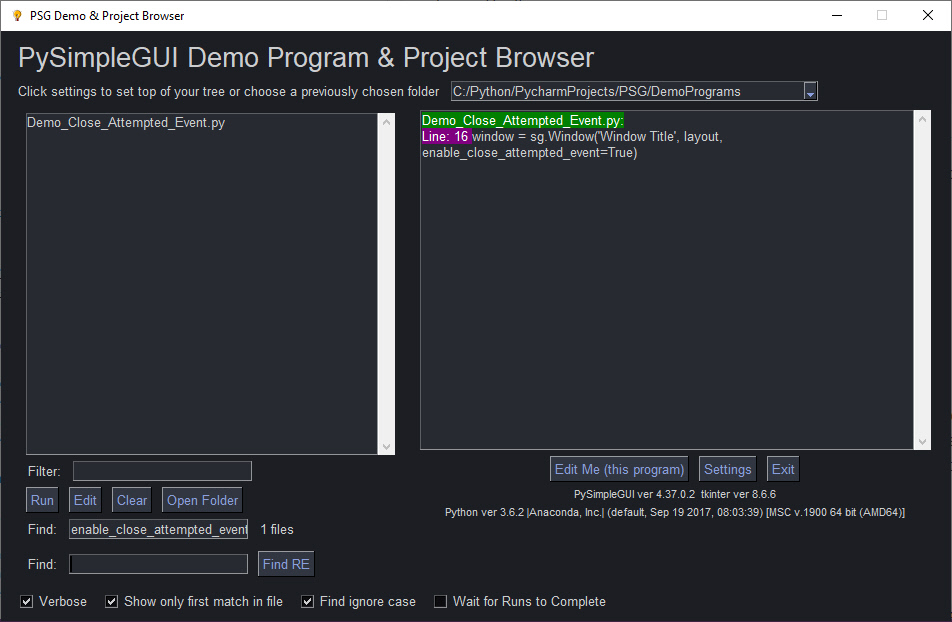

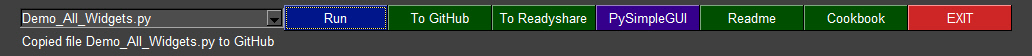

sg.mainutilities - upgrade to the GitHub version in 1 click. Lots of good stuff built-into FreeSimpleGUI- Demo Browser - Navigate the 315+ Demo Programs easily. Search, execute, edit all from one application

- Cookbook - There have been a number of updates in 2021

- This document has some sections new such as the User Settings APIs

Dynamic Windows

- Making parts of windows expand/contract with the window.

- Swap out or collapse sections

- More parms in Elements to help with justification

- New

Push&VPushElements trivialize justification

Threading

One simple call, write_event_value, solves threading issues.

Not ready for the threading module but need to run a thread? Use window.perform_long_operation to use threads. One call and done.

What's Old?

The old parts of this documentation are the images. The good news is that things look better than you see here. Themes have made Windows colorful in 1 line of code.

Looking for a GUI package? Are you...

- looking to take your Python code from the world of command lines and into the convenience of a GUI?

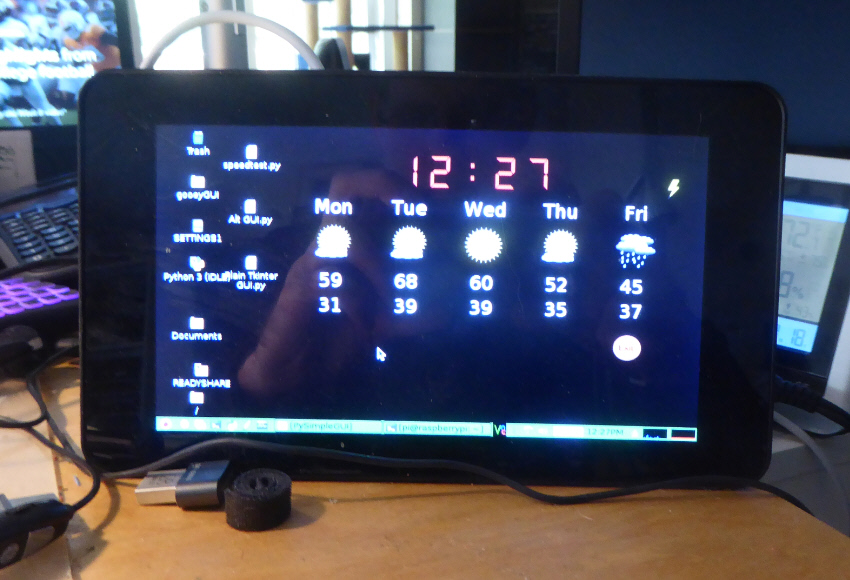

- sitting on a Raspberry Pi with a touchscreen that's going to waste because you don't have the time to learn a GUI SDK?

- into Machine Learning and are sick of the command line?

- an IT guy/gal that has written some cool tools but due to corporate policies are unable to share unless it is an EXE file?

- wanting to share your program with your friends or families (that aren't so freakish that they have Python running)

- wanting to run a program in your system tray?

- a teacher wanting to teach your students how to program using a GUI?

- a student that wants to put a GUI onto your project that will blow away your teacher?

- looking for a GUI package that is "supported" and is being constantly developed to improve it?

- longing for documentation and scores of examples?

Look no further, you've found your GUI package.

The basics

- Create windows that look and operate identically to those created directly with tkinter, Qt, WxPython, and Remi.

- Requires 1/2 to 1/10th the amount of code as underlying frameworks.

- One afternoon is all that is required to learn the FreeSimpleGUI package and write your first custom GUI.

- Students can begin using within their first week of Python education.

- No callback functions. You do not need to write the word

classanywhere in your code. - Access to nearly every underlying GUI Framework's Widgets.

- Supports both Python 2.7 & 3 when using tkinter.

- Supports both PySide2 and PyQt5 (limited support).

- Effortlessly move across tkinter, Qt, WxPython, and the Web (Remi) by changing only the import statement.

- The only way to write both desktop and web-based GUIs at the same time in Python.

- Developed from nothing as a pure Python implementation with Python friendly interfaces.

- Run your program in the System Tray using WxPython. Or, change the import and run it on Qt with no other changes.

- Works with Qt Designer.

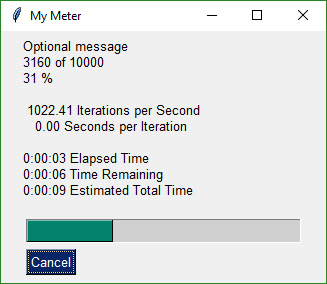

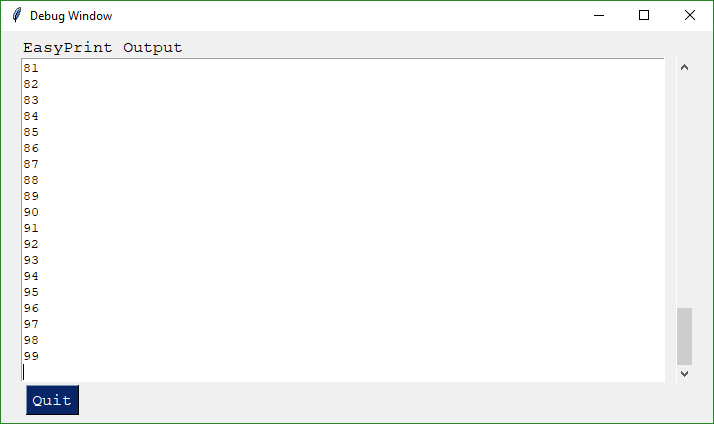

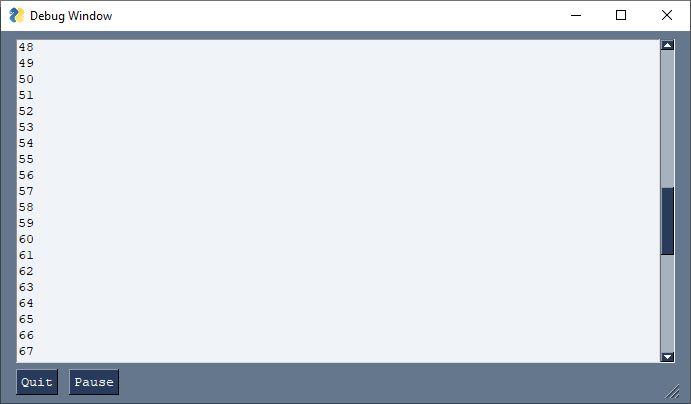

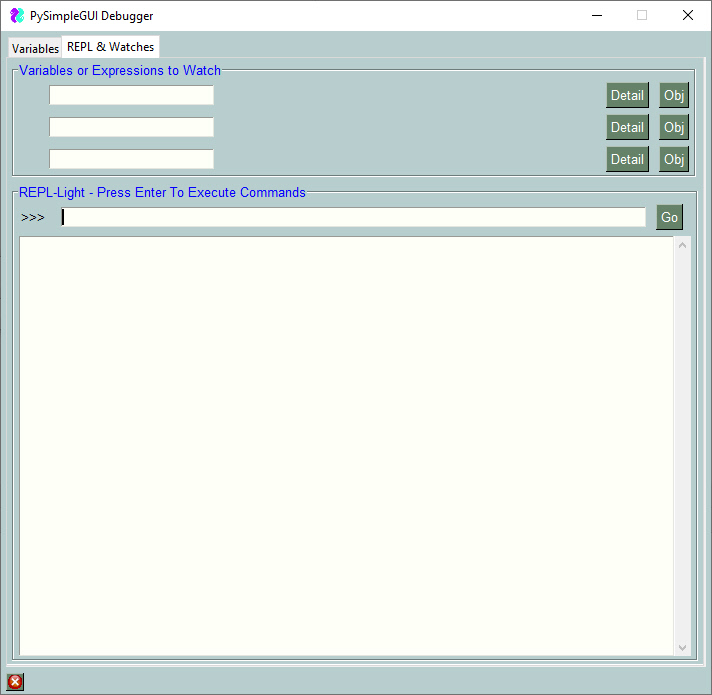

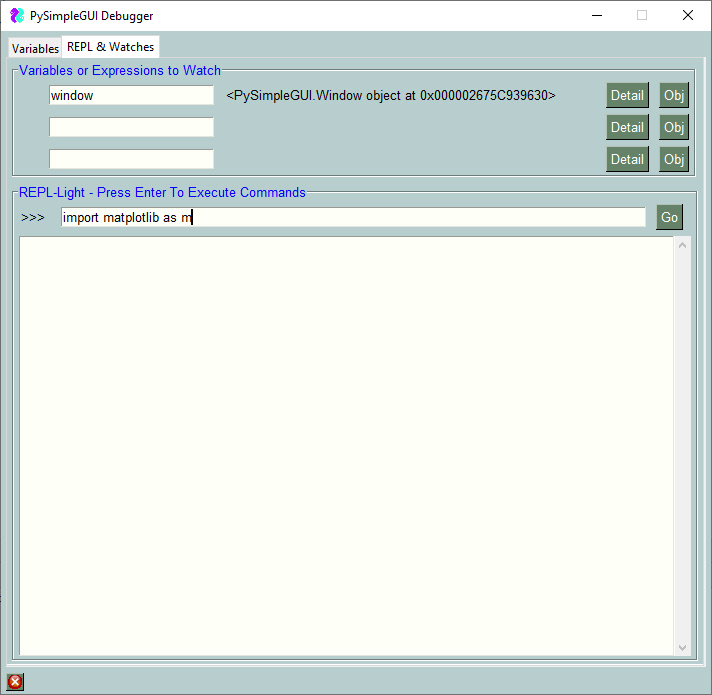

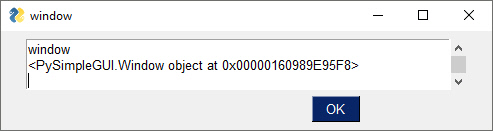

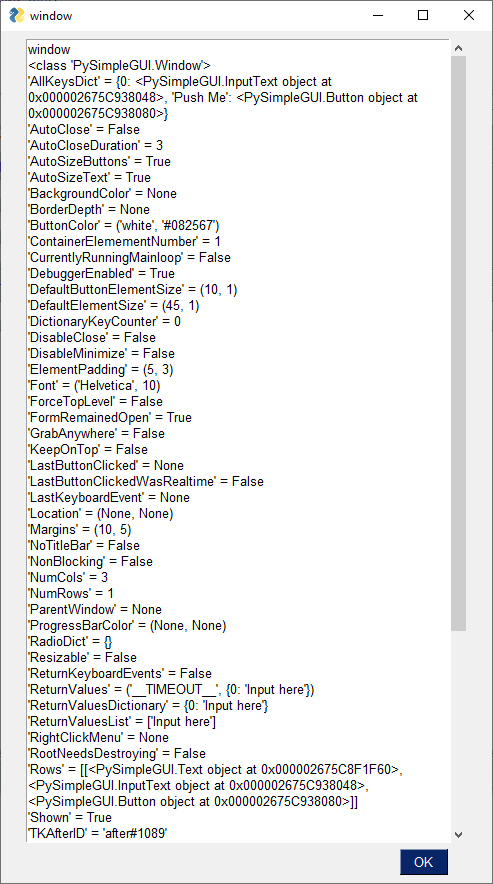

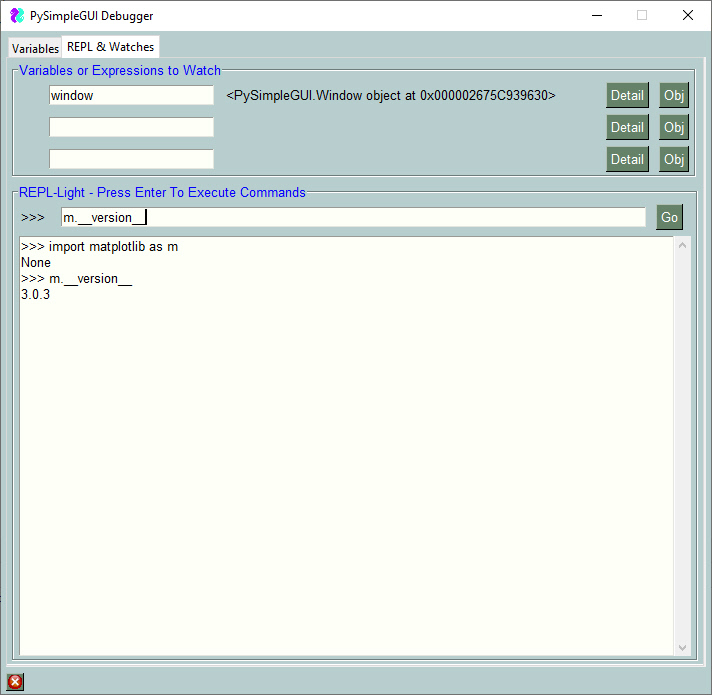

- Built in Debugger.

- Actively maintained and enhanced - 4 ports are underway, all being used by users.

- Corporate as well as home users.

- Appealing to both newcomers to Python and experienced Pythonistas.

- The focus is entirely on the developer (you) and making their life easier, simplified, and in control.

- 170+ Demo Programs teach you how to integrate with many popular packages like OpenCV, Matplotlib, PyGame, etc.

- 200 pages of documentation, a Cookbook, and built-in help using docstrings. In short it's heavily documented.

GUI Development does not have to be difficult nor painful. It can be (and is) FUN

START HERE - User Manual with Table of Contents

ReadTheDocs <------ THE best place to read the docs due to TOC, all docs in 1 place, and better formatting. START here in your education. Easy to remember PySimpleGUI.org.

The Call Reference documentation is located on the same ReadTheDocs page as the main documentation, but it's on another tab that you'll find across the top of the page.

The quick way to remember the documentation addresses is to use these addresses:

http://docs.PySimpleGUI.org http://calls.PySimpleGUI.org

Quick Links To Help and The Latest News and Releases

Homepage - Lastest Readme and Code - GitHub Easy to remember: PySimpleGUI.com

Latest Demos and Master Branch on GitHub

The YouTube videos - If you like instructional videos, there are over 15 videos made by PySimpleGUI project over the first 18 months. In 2020 a new series was begun. As of May 2020 there are 12 videos completed so far with many more to go.... - PySimpleGUI 2020 - The most up to date information about PySimpleGUI - 5 part series of basics - 10 part series of more detail - The Naked Truth (An update on the technology) - There are numerous short videos also on that channel that demonstrate PySimpleGUI being used

YouTube Videos made by others. These have much higher production values than the above videos.

- A fantastic tutorial PySimpleGUI Concepts - Video 1

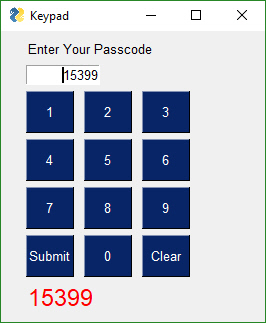

- Build a calculator Python Calculator with GUI | PySimpleGUI | Texas Instruments DataMath II

- Notepad Notepad in Python - PySimpleGUI

- File Search Engine File Search Engine | Project for Python Portfolio with GUI | PySimpleGUI

About The FreeSimpleGUI Documentation System

This User's Manual (also the project's readme) is one vital part of the FreeSimpleGUI programming environment. The best place to read it is at http://www.FreeSimpleGUI.org

If you are a professional or skilled in how to develop software, then you understand the role of documentation in the world of technology development. Use it, please.

It WILL be required, at times, for you to read or search this document in order to be successful.

Using Stack Overflow and other sites to post your questions has resulted in advice given by a lot of users that have never looked at the package and are sometimes just flat bad advice. When possible, post an Issue on this GitHub. Definitely go through the Issue checklist. Take a look through the docs again.

There are 5 resources that work together to provide you with the fastest path to success. They are:

- This User's Manual

- The Cookbook

- The 170+ Demo Programs

- Docstrings enable you to access help directly from Python or your IDE

- Searching the GitHub Issues as a last resort (search both open and closed issues)

Pace yourself. The initial progress is exciting and FAST PACED. However, GUIs take time and thought to build. Take a deep breath and use the provided materials and you'll do fine. Don't skip the design phase of your GUI after you run some demos and get the hang of things. If you've tried other GUI frameworks before, successful or not, then you know you're already way ahead of the game using FreeSimpleGUI versus the underlying GUI frameworks. It may feel like the 3 days you've been working on your code has been forever, but by comparison of 3 days learning Qt, FreeSimpleGUI will look trivial to learn.

It is not by accident that this section, about documentation, is at the TOP of this document.

This documentation is not HUGE in length for a package this size. In fact it's still one document and it's the readme for the GitHub. It's not written in complex English. It is understandable by complete beginners. And pressing Control+F is all you need to do to search this document. USUALLY you'll find less than 6 matches.

Documentation and Demos Get Out of Date

Sometimes the documentation doesn't match exactly the version of the code you're running. Sometimes demo programs haven't been updated to match a change made to the SDK. Things don't happen simultaneously generally speaking. So, it may very well be that you find an error or inconsistency or something no longer works with the latest version of an external library.

If you've found one of these problems, and you've searched to make sure it's not a simple mistake on your part, then by ALL means log an Issue on the GitHub. Don't be afraid to report problems if you've taken the simple steps of checking out the docs first.

Platforms

Hardware and OS Support

FreeSimpleGUI runs on Windows, Linux and Mac, just like tkinter, Qt, WxPython and Remi do. If you can get the underlying GUI Framework installed / running on your machine then FreeSimpleGUI will also run there.

Hardware

- PC's, Desktop, Laptops

- Macs of all types

- Raspberry Pi

- Android devices like phones and tablets

- Virtual machine online (no hardware) - repl.it

OS

- Windows 7, 8, 10, 11

- Linux on PC - Tested on several distributions

- Linux on Raspberry Pi

- Linux on Android - Can use either Termux or PyDroid3

- Mac OS

Output Devices

In addition to running as a desktop GUI, you can also run your GUI in a web browser by running PySimpleGUIWeb.

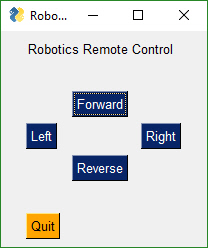

This is ideal for "headless" setups like a Raspberry Pi that is at the core of a robot or other design that does not have a normal display screen. For these devices, run a PySimpleGUIWeb program that never exits.

Then connect to your application by going to the Pi's IP address (and port #) using a browser and you'll be in communication with your application. You can use it to make configuration changes or even control a robot or other piece of hardware using buttons in your GUI.

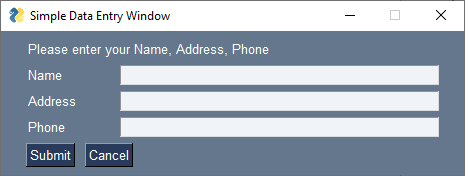

A Complete PySimpleGUI Program (Getting The Gist)

Before diving into details, here's a description of what PySimpleGUI is/does and why that is so powerful.

You keep hearing "custom window" in this document because that's what you're making and using... your own custom windows.

ELEMENTS is a word you'll see everywhere... in the code, documentation, ... Elements == PySimpleGUI's Widgets. As to not confuse a tkinter Button Widget with a PySimpleGUI Button Element, it was decided that PySimpleGUI's Widgets will be called Elements to avoid confusion.

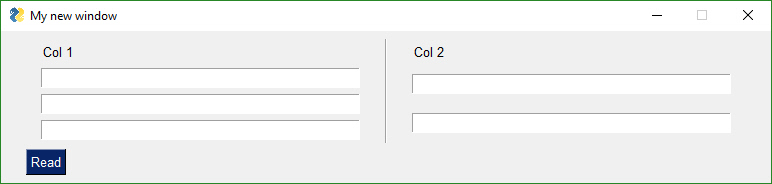

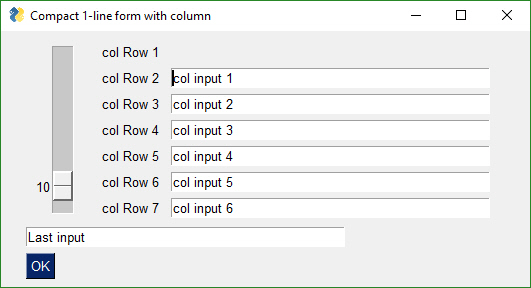

Wouldn't it be nice if a GUI with 3 "rows" of Elements were defined in 3 lines of code? That's exactly how it's done. Each row of Elements is a list. Put all those lists together and you've got a window.

What about handling button clicks and stuff. That's 4 lines of the code below beginning with the while loop.

Now look at the layout variable and then look at the window graphic below. Defining a window is taking a design you can see visually and then visually creating it in code. One row of Elements = 1 line of code (can span more if your window is crowded). The window is exactly what we see in the code. A line of text, a line of text and an input area, and finally ok and cancel buttons.

This makes the coding process extremely quick and the amount of code very small

import FreeSimpleGUI as sg

sg.theme('DarkAmber') # Add a little color to your windows

# All the stuff inside your window. This is the PSG magic code compactor...

layout = [ [sg.Text('Some text on Row 1')],

[sg.Text('Enter something on Row 2'), sg.InputText()],

[sg.OK(), sg.Cancel()]]

# Create the Window

window = sg.Window('Window Title', layout)

# Event Loop to process "events"

while True:

event, values = window.read()

if event in (sg.WIN_CLOSED, 'Cancel'):

break

window.close()

You got to admit that the code above is a lot more "fun" looking that tkinter code you've studied before. Adding stuff to your GUI is trivial. You can clearly see the "mapping" of those 3 lines of code to specific Elements laid out in a Window. It's not a trick. It's how easy it is to code in PySimpleGUI. With this simple concept comes the ability to create any window layout you wish. There are parameters to move elements around inside the window should you need more control.

It's a thrill to complete your GUI project way ahead of what you estimated. Some people take that extra time to polish their GUI to make it even nicer, adding more bells and whistles because it's so easy and it's a lot of fun to see success after success as you write your program.

Some are more advanced users and push the boundaries out and extend PySimpleGUI using their own extensions.

Others, like IT people and hackers, are busily cranking out GUI program after GUI program, and creating tools that others can use. Finally, there's an easy way to throw a GUI onto your program and give it to someone. It's a pretty big leap in capability for some people. It's GREAT to hear these successes. It's motivating for everyone in the end. Your success can easily motivate the next person to give it a try and also potentially be successful.

Usually, there's a one to one mapping of a PySimpleGUI Element to a GUI Widget. A "Text Element" in PySimpleGUI == "Label Widget" in tkinter. What remains constant for you across all PySimpleGUI platforms is that no matter what the underlying GUI framework calls the thing that places text in your window, you'll always use the PySimpleGUI Text Element to access it.

The final bit of magic is in how Elements are created and changed.

So far you've seen simple layouts with no customization of the Elements. Customizing and configuring Elements is another place PySimpleGUI utilizes the Python language to make your life easier.

What about Elements that have settings other than the standard system settings? What if I want my Text to be blue, with a Courier font on a green background. It's written quite simply:

Text('This is some text', font='Courier 12', text_color='blue', background_color='green')

The Python named parameters are extensively in PySimpleGUI. They are key in making the code compact, readable, and trivial to write.

As you'll learn in later sections that discuss the parameters to the Elements, there are a LOT of options available to you should you choose to use them. The Text Element has 15 parameters that you can change. This is one reason why PyCharm is suggested as your IDE... it does a fantastic job of displaying documentation as you type in your code.

That's The Basics

What do you think? Easier so far than your previous run-ins with GUIs in Python? Some programs, many in fact, are as simple as this example has been.

But PySimpleGUI certainly does not end here. This is the beginning. The scaffolding you'll build upon.

The Underlying GUI Frameworks & Status of Each

At the moment there are 4 actively developed and maintained "ports" of PySimpleGUI. These include:

- tkinter - Fully complete

- Qt using Pyside2 - Alpha stage. Not all features for all Elements are done

- WxPython - Development stage, pre-releaser. Not all Elements are done. Some known problems with multiple windows

- Remi (Web browser support) - Development stage, pre-release.

While PySimpleGUI, the tkinter port, is the only 100% completed version of PySimpleGUI, the other 3 ports have a LOT of functionality in them and are in active use by a large portion of the installations. You can see the number of Pip installs at the very top of this document to get a comparison as to the size of the install base for each port. The "badges" are right after the logo.

The Chain Link Fence

Maybe you've heard the "Walled Garden" term before. It's a boxing in effect.

While PySimpleGUI has a well-established parameter so you know where the edges are, there is no wall between you and the rest of the GUI framework. There's a chain link fence that's easy to reach through and get full access to the underlying frameworks.

The net result - it's easy to expand features that are not yet available in PySimpleGUI and easy to remove them too. Maybe the Listbox Element doesn't have a mode exposed that you want to enable. No problem, you can access the underlying Listbox Widget and make what is likely 1 or 2 calls and be done.

The PySimpleGUI "Family"

What's The Big Deal? What is it?

PySimpleGUI wraps tkinter, Qt, WxPython, and Remi so that you get all the same widgets, but you interact with them in a more friendly way that's common across the ports.

What does a wrapper do (Yo! PSG in the house!)? It does the layout, boilerplate code, creates and manages the GUI Widgets for you and presents you with a simple, efficient interface. Most importantly, it maps the Widgets in tkinter/Qt/Wx/Remi into FreeSimpleGUI Elements. Finally, it replaces the GUIs' event loop with one of our own.

You've seen examples of the code already. The big deal of all this is that anyone can create a GUI simply and quickly that matches GUIs written in the native GUI framework. You can create complex layouts with complex element interactions. And, that code you wrote to run on tkinter will also run on Qt by changing your import statement.

If you want a deeper explanation about the architecture of PySimpleGUI, you'll find it on ReadTheDocs in the same document as the Readme & Cookbook. There is a tab at the top with labels for each document.

The "Ports"

There are distinct ports happening as mentioned above. Each has its own location on GitHub under the main project. Heac has its own Readme which is an augmentation of this document... they are meant to be used together.

FreeSimpleGUI is released on PyPI as 5 distinct packages. 1. FreeSimpleGUI - tkinter version 3. FreeSimpleGUIWx - WxPython version 4. FreeSimpleGUIQt - PySided2 version 5. FreeSimpleGUIWeb - The web (Remi) version

You will need to install them separately

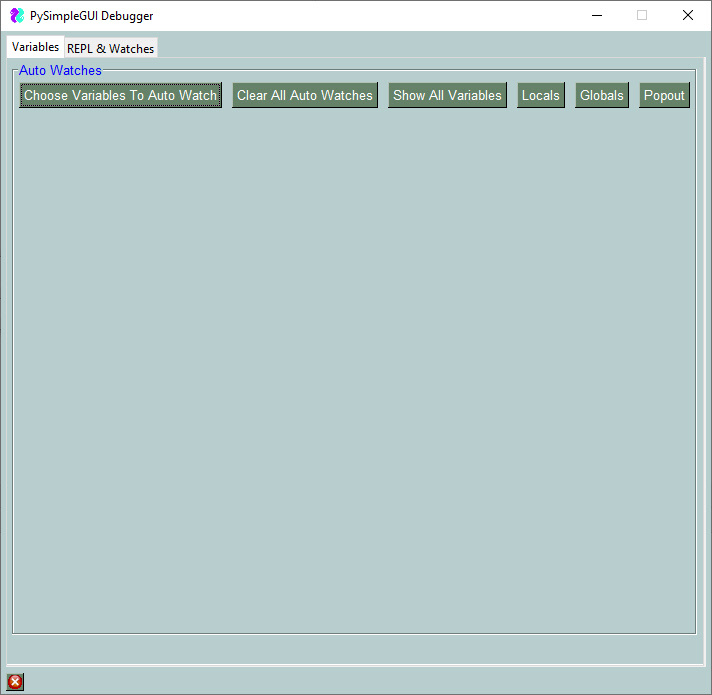

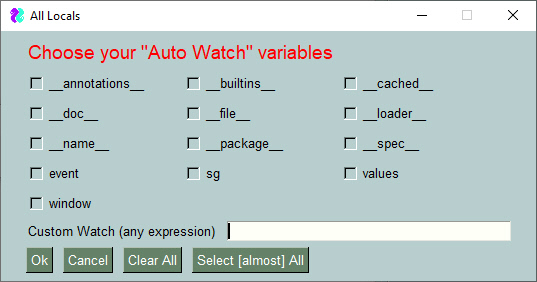

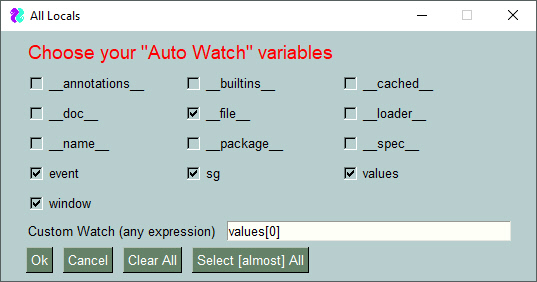

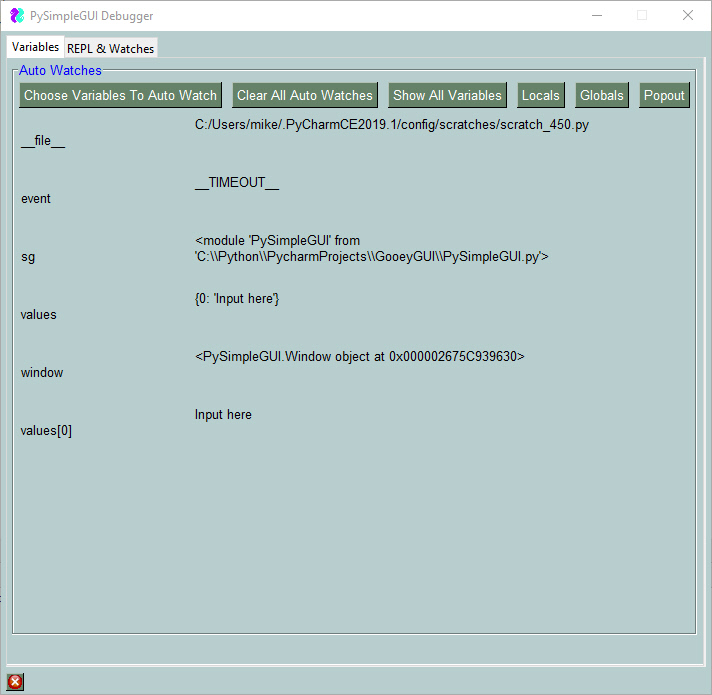

There is also an accompanying debugger known as imwatchingyou. If you are running the tkinter version of FreeSimpleGUI, you will not need to install the debugger as there is a version embedded directly into FreeSimpleGUI.

Qt Version

Qt was the second port after tkinter. It is the 2nd most complete with the original FreeSimpleGUI (tkinter) being the most complete and is likely to continue to be the front-runner. All of the Elements are available on FreeSimpleGUIQt.

As mentioned previously each port has an area. For Qt, you can learn more on the FreeSimpleGUIQt GitHub site. There is a separate Readme file for the Qt version that you'll find there. This is true for all of the FreeSimpleGUI ports.

Give it a shot if you're looking for something a bit more "modern". FreeSimpleGUIQt is currently in Alpha. All of the widgets are operational but some may not yet be full-featured. If one is missing and your project needs it, log an Issue. It's how new features are born.

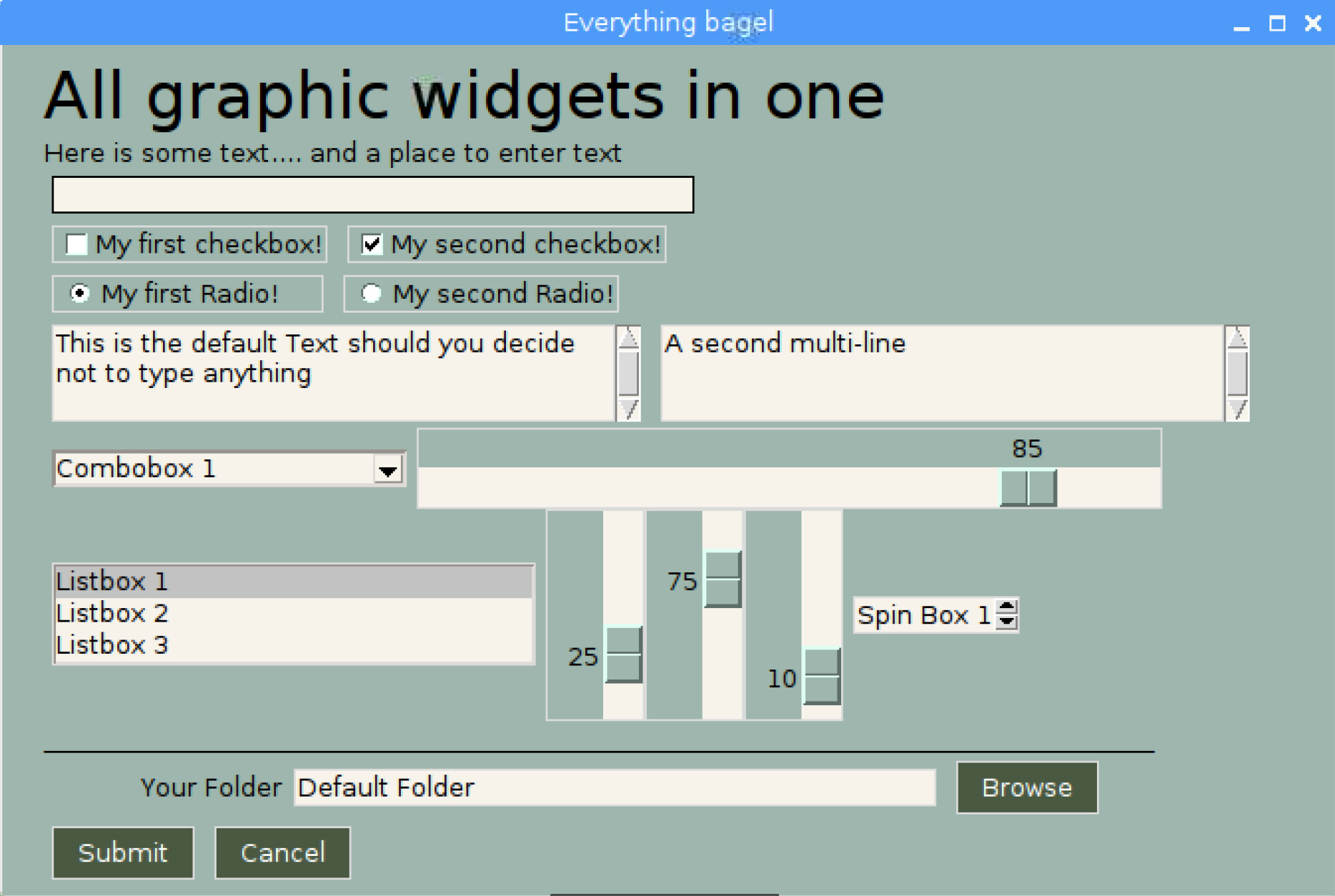

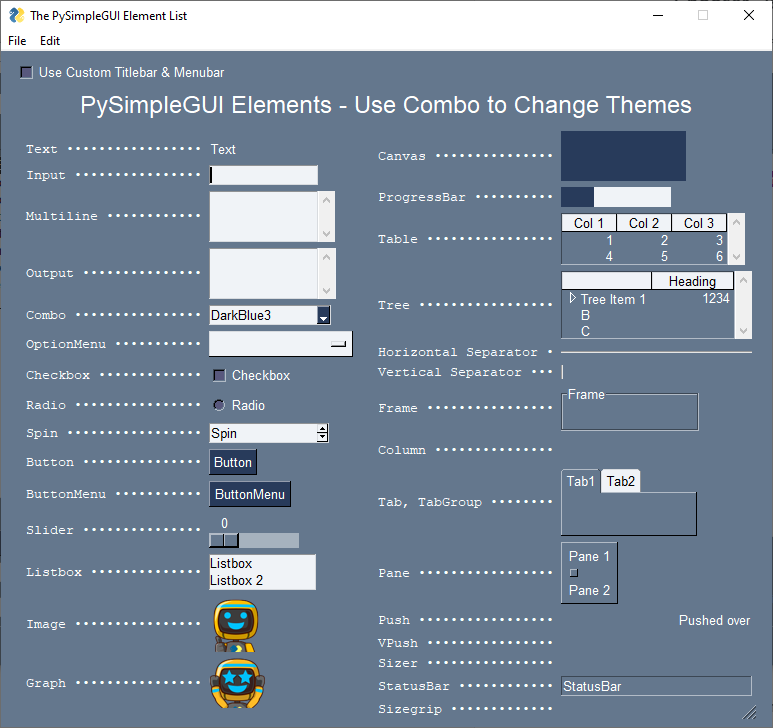

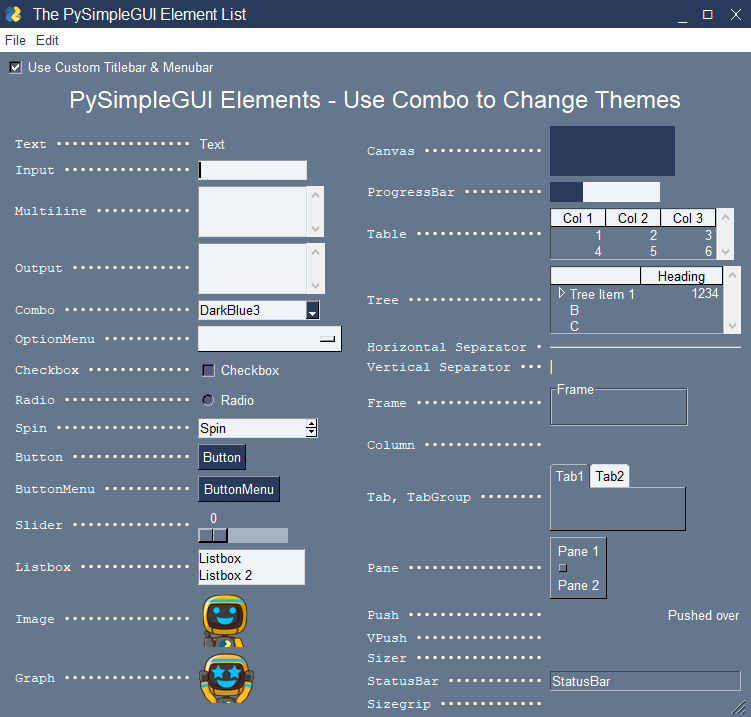

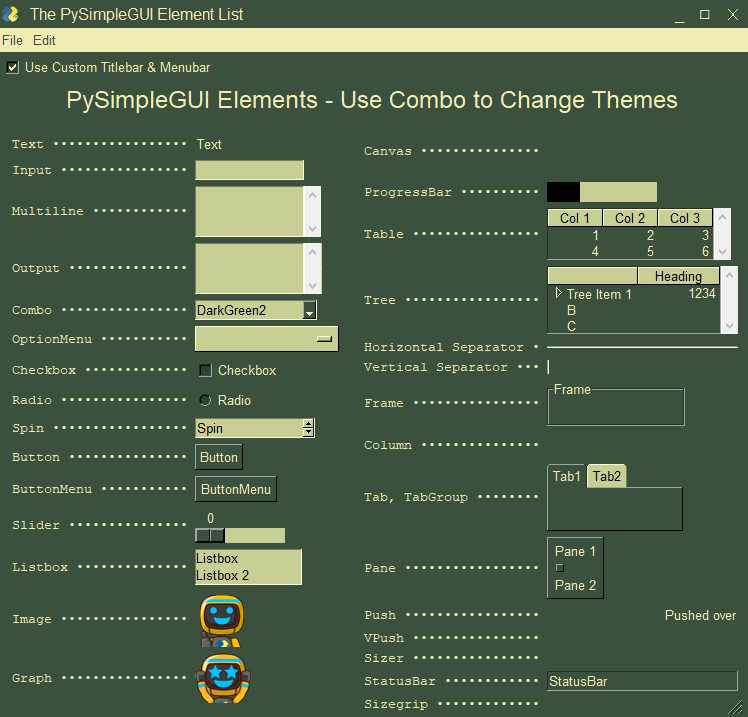

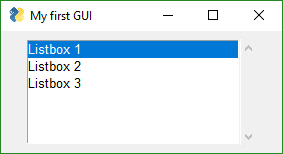

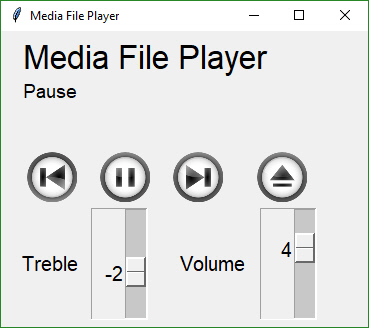

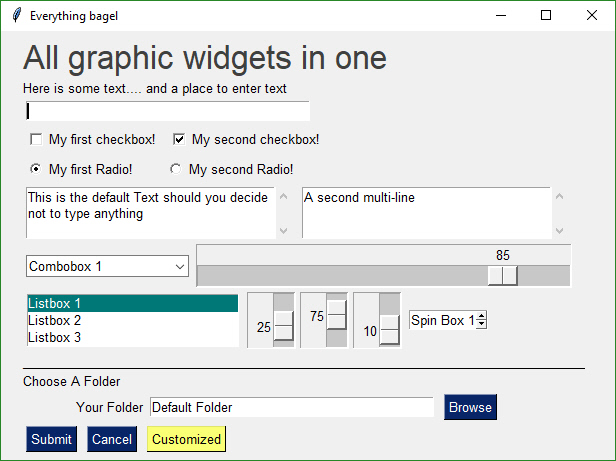

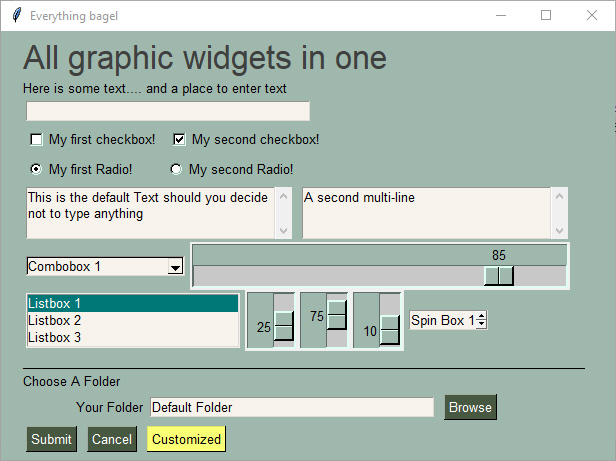

Here is a summary of the Qt Elements with no real effort spent on design clearly. It's an example of the "test harness" that is a part of each port. If you run the FreeSimpleGUI.py file itself then you'll see one of these tests.

As you can see, you've got a full array of GUI Elements to work with. All the standard ones are there in a single window. So don't be fooled into thinking FreeSimpleGUIQt is barely working or doesn't have many widgets to choose from. You even get TWO "Bonus Elements" - Dial and Stretch

WxPython Version

FreeSimpleGUIWx GitHub site. There is a separate Readme file for the WxPython version.

Started in late December 2018 FreeSimpleGUIWx started with the SystemTray Icon feature. This enabled the package to have one fully functioning feature that can be used along with tkinter to provide a complete program. The System Tray feature is complete and working very well. It was used not long ago in a corporate setting and has been performing with few problems reported.

The Windowing code was coming together with Reads operational. The elements were getting completed on a regular basis. But I ran into multiwindow problems. And it was at about this time that Remi was suggested as a port.

Remi (the "web port") overnight leapt the WxPython effort and Web became a #1 priority and continues to be. The thought is that the desktop was well represented with FreeSimpleGUI, FreeSimpleGUIQt, and FreeSimpleGUIWx. Between those ports is a solid windowing system and 2 system tray implementations and a nearly feature complete Qt effort. So, the team was switched over to FreeSimpleGUIWeb.

Web Version (Remi)

FreeSimpleGUIWeb GitHub site. There is a separate Readme file for the Web version.

New for 2019, FreeSimpleGUIWeb. This is an exciting development! FreeSimpleGUI in your Web Browser!

The underlying framework supplying the web capability is the Python package Remi. https://github.com/dddomodossola/remi Remi provides the widgets as well as a web server for you to connect to. It's an exiting new platform to be running on and has temporarily bumped the WxPython port from the highest priority. FreeSimpleGUIWeb is the current high priority project.

Use this solution for your Pi projects that don't have anything connected in terms of input devices or display. Run your Pi in "headless" mode and then access it via the Web interface. This allows you to easily access and make changes to your Pi without having to hook up anything to it.

*It's not meant to "serve up web pages"*

FreeSimpleGUIWeb is first and foremost a GUI, a program's front-end. It is designed to have a single user connect and interact with the GUI.

If more than 1 person connects at a time, then both users will see the exact same stuff and will be interacting with the program as if a single user was using it.

Android Version

FreeSimpleGUI runs on Android devices with the help of either the PyDroid3 app or the Termux app. Both are capable of running tkinter programs which means both are capable of running FreeSimpleGUI.

To use with PyDroid3 you will need to add this import to the top of all of your FreeSimpleGUI program files:

import tkinter

This evidently triggers PyDroid3 that the application is going to need to use the GUI.

You will also want to create your windows with the location parameter set to (0,0).

Here's a quick demo that uses OpenCV2 to display your webcam in a window that runs on PyDroid3:

import tkinter

import cv2, FreeSimpleGUI as sg

USE_CAMERA = 0 # change to 1 for front facing camera

window, cap = sg.Window('Demo Application - OpenCV Integration', [[sg.Image(filename='', key='image')], ], location=(0, 0), grab_anywhere=True), cv2.VideoCapture(USE_CAMERA)

while window(timeout=20)[0] != sg.WIN_CLOSED:

window['image'](data=cv2.imencode('.png', cap.read()[1])[1].tobytes())

You will need to pip install opencv-python as well as FreeSimpleGUI to run this program.

Also, you must be using the Premium, yes paid, version of PyDroid3 in order to run OpenCV. The cost is CHEAP when compared to the rest of things in life. A movie ticket will cost you more. Which is more fun, seeing your Python program running on your phone and using your phone's camera, or some random movie currently playing? From experience, the Python choice is a winner. If you're cheap, well, then you won't get to use OpenCV. No, there is no secret commercial pact between the FreeSimpleGUI project and the PyDroid3 app team.

Source code compatibility

In theory, your source code is completely portable from one platform to another by simply changing the import statement. That's the GOAL and surprisingly many times this 1-line change works. Seeing your code run on tkinter, then change the import to import FreeSimpleGUIWeb as sg and instead of a tkinter window, up pops your default browser with your window running on it is an incredible feeling.

But, caution is advised. As you've read already, some ports are further along than others. That means when you move from one port to another, some features may not work. There also may be some alignment tweaks if you have an application that precisely aligns Elements.

What does this mean, assuming it works? It means it takes a trivial amount of effort to move across GUI Frameworks. Don't like the way your GUI looks on tkinter? No problem, change over to try FreeSimpleGUIQt. Made a nice desktop app but want to bring it to the web too? Again, no problem, use FreeSimpleGUIWeb.

FreeSimpleGUI (tkinter based)

The primary FreeSimpleGUI port works very well on repl.it due to the fact they've done an outstanding job getting tkinter to run on these virtual machines. Creating a program from scratch, you will want to choose the "Python with tkinter" project type.

The virtual screen size for the rendered windows isn't very large, so be mindful of your window's size or else you may end up with buttons you can't get to.

You may have to "install" the FreeSimpleGUI package for your project. If it doesn't automatically install it for you, then click on the cube along the left edge of the browser window and then type in FreeSimpleGUI or FreeSimpleGUIWeb depending on which you're using. ``[

FreeSimpleGUIWeb (Remi based)

For FreeSimpleGUIWeb programs you run using repl.it will automatically download and install the latest FreeSimpleGUIWeb from PyPI onto a virtual Python environment. All that is required is to type import FreeSimpleGUIWeb you'll have a Python environment up and running with the latest PyPI release of FreeSimpleGUIWeb.

Macs](https://freesimplegui.readthedocs.io/en/latest)``

It's surprising that Python GUI code is completely cross platform from Windows to Mac to Linux. No source code changes. This is true for both FreeSimpleGUI and FreeSimpleGUIQt.

Historically, PySimpleGUI using tkinter have struggled on Macs. This was because of a problem setting button colors on the Mac. However, two events has turned this problem around entirely.

- Use of ttk Buttons for Macs

- Ability for Mac users to install Python from python.org rather than the Homebrew version with button problems

FreeSimpleGUI supports Macs, Linux, and Windows equally well. They all are able to use the "Themes" that automatically add color to your windows.

Be aware that Macs default to using ttk buttons. You can override this setting at the Window and Button levels. If you installed Python from python.org, then it's likely you can use the non-ttk buttons should you wish.

Learning Resources

This document.... you must be willing to read this document if you expect to learn and use PySimpleGUI.

The PySimpleGUI, Developer-Centric Model

You may think that you're being fed a line about all these claims that PySimpleGUI is built specifically to make your life easier and a lot more fun than the alternatives.... especially after reading the bit above about reading this manual.

Psychological Warfare

Brainwashed. Know that there is an active campaign to get you to be successful using PySimpleGUI. The "Hook" to draw you in and keep you working on your program until you're satisfied is to work on the dopamine in your brain. Yes, your a PySimpleGUI rat, pressing on that bar that drops a food pellet reward in the form of a working program.

The way this works is to give you success after success, with very short intervals between. For this to work, what you're doing must work. The code you run must work. Make small changes to your program and run it over and over and over instead of trying to do one big massive set of changes. Turn one knob at a time and you'll be fine.

Find the keyboard shortcut for your IDE to run the currently shown program so that running the code requires 1 keystroke. On PyCharm, the key to run what you see is Control + Shift + F10. That's a lot to hold down at once. I programmed a hotkey on my keyboard so that it emits that combination of keys when I press it. Result is a single button to run.

Tools

These tools were created to help you achieve a steady stream of these little successes.

- This readme and its example pieces of code

- The Cookbook & eCoobook - Copy, paste, run, success

- Demo Programs - Copy these small programs to give yourself an instant head-start

- Documentation shown in your IDE (docstrings) means you do not need to open any document to get the full assortment of options available to you for each Element & function call

The initial "get up and running" portion of PySimpleGUI should take you less than 5 minutes (the 5 minute challenge). The goal is 5 minutes from your decision "I'll give it a try" to having your first window up on the screen. "Oh wow, it was that easy?!"

The primary learning paths for PySimpleGUI are:

- The Documentation

- Resist the urge to "Google It"

- The old-school way, "Read the Documenation", for this project, will be the most efficient path.

- PySimpleGUI Documentation - http://www.PySimpleGUI.org

- Here you will find the main doc, the Cookbook, the Call Reference, the Readme... all in 1 location.

- This readme document on GitHub and in the main documentation

- PySimpleGUI GitHub: http://www.PySimpleGUI.com

- The Cookbook - Recipes to get you going and quick

- http://Cookbook.PySimpleGUI.org

- The online Interactive eCookbook is also available - http://eCookbook.PySimpleGUI.org

- The Demo Programs - Start hacking on one of these running solutions

- http://Demos.PySimpleGUI.org

- The easiest way to obtain and use them is by pip installing

psgdemos

- The Udemy Course! "The Official PySimpleGUI Course"

- The is ONE and only 1 video course on the Internet that helps the PySimpleGUI financially.

- http://udemy.pysimplegui.org/

- There are 61 lessons that will teach you all aspects of PySimpleGUI

- It was a year in the making and covers features up through end of 2021

- It's the best course I've ever written and recorded (says Mike). Each lesson is compact, consise, focused, easy to understand

- The YouTube videos - If you like instructional videos, there are 15+ videos.

- Caution is advised... these videos are from 2020. Much has changed since they were made. They are still quite valid as what you're taught will work. But, you're missing 2 years of intense development that are not represented in these lessons. The Udemy course is a more complete and current course.

- 2020 to 2022 update - https://youtu.be/lRuvKfilJnA-Lists a few of the many changes to PySimpleGUI since the 2020 lessons were recorded.

- 5 part series of basics

- 10 part series of more detail

Everything is geared towards giving you a "quick start" whether that be a Recipe or a Demo Program. The idea is to give you something running and let you hack away at it. As a developer this saves tremendous amounts of time.

You start with a working program, a GUI on the screen. Then have at it. If you break something ("a happy little accident" as Bob Ross put it), then you can always backtrack a little to a known working point.

A high percentage of users report both learning PySimpleGUI and completing their project in a single day.

This isn't a rare event and it's not bragging. GUI programming doesn't HAVE to be difficult by definition and PySimpleGUI has certainly made it much much more approachable and easier (not to mention simpler).

But there will be times that you need to read documentation, look at examples, when pushing into new, unknown territory. Don't guess... or more specifically, don't guess and then give up when it doesn't work.

This Documentation, Call Reference and Cookbook

The quickest way to the docs is to visit: http://www.PySimpleGUI.org

You will be auto-forwarded to the right destination. There are multiple tabs on ReadTheDocs.

The call reference is an important document as it explains every call and every parameter. Note that this same information is available to you via docstrings so that as you are writing your code, you can read the documentation without ever leaving your IDE (e.g. PyCharm)

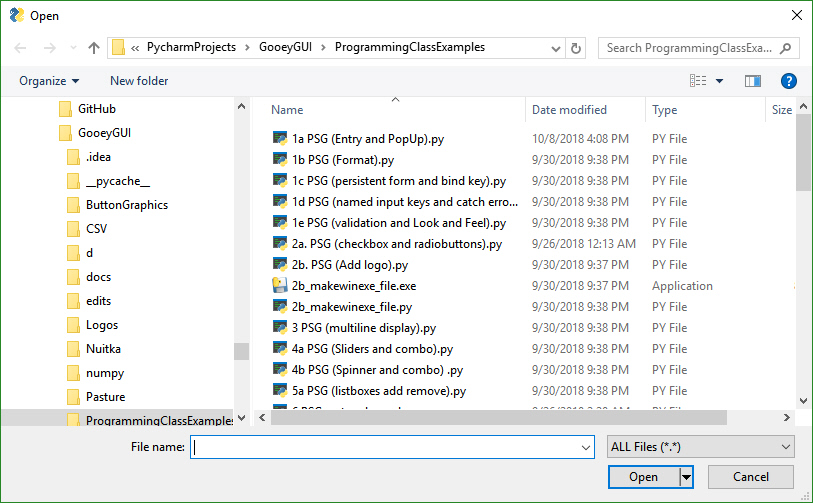

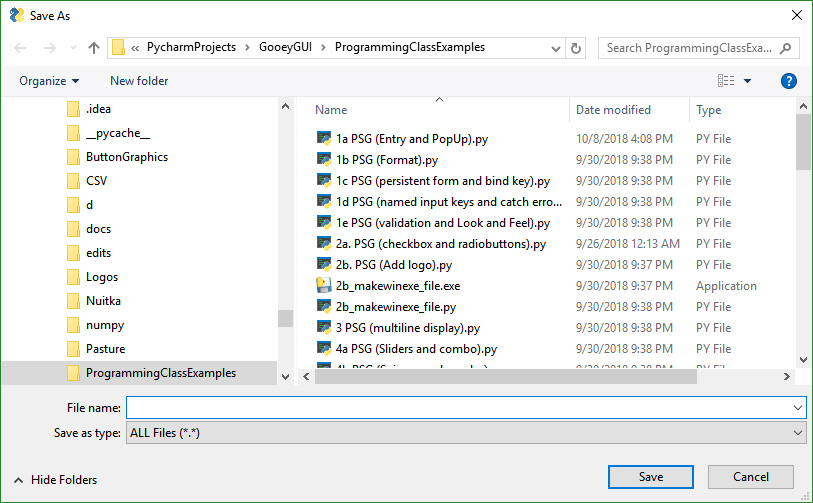

Demo Programs

The GitHub repo has the Demo Programs. There are ones built for plain PySimpleGUI that are usually portable to other versions of PySimpleGUI. And there are some that are associated with one of the other ports.

As of the start of 2022 there are over 300 Demo Programs.

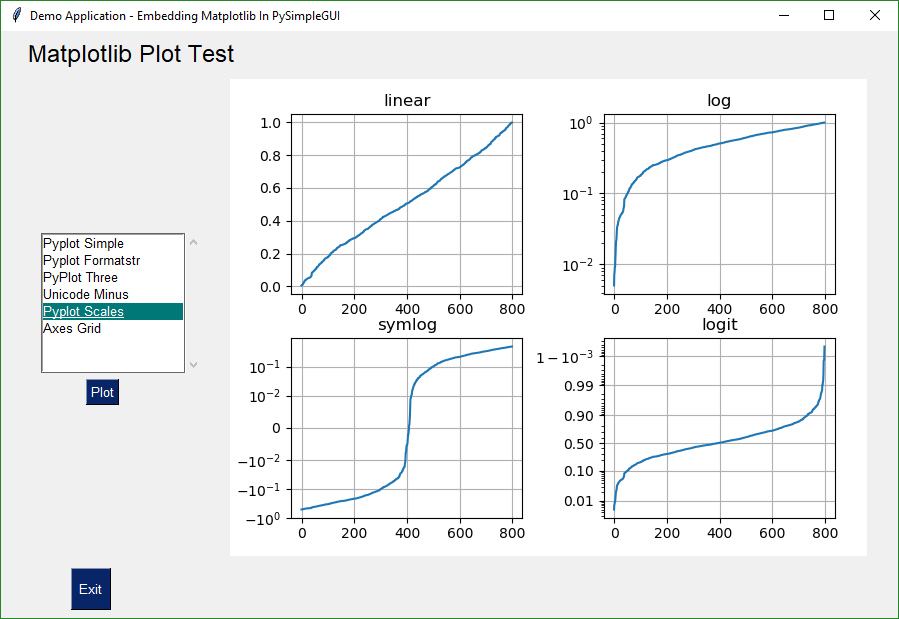

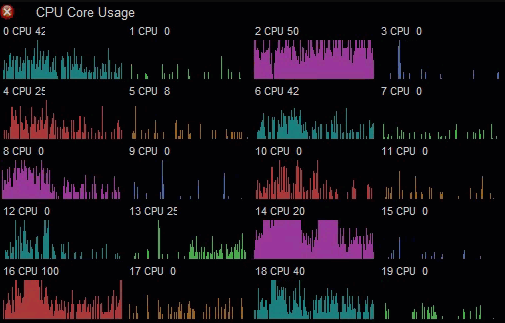

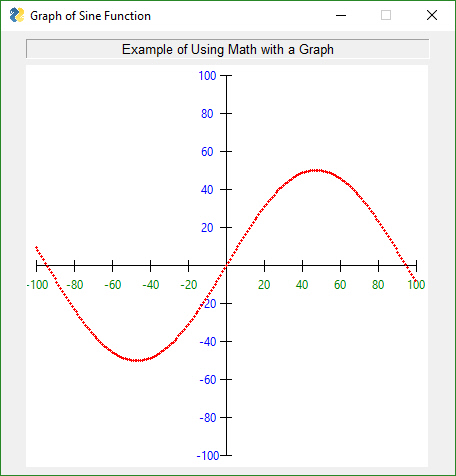

These programs demonstrate to you how to use the Elements and how to integrate PySimpleGUI with some of the popular open source technologies such as OpenCV, PyGame, PyPlot, and Matplotlib to name a few.

Many Demo Programs that are in the main folder will run on multiple ports of PySimpleGUI. There are also port-specific Demo Programs. You'll find those in the folder with the port. So, Qt specific Demo Programs are in the PySimpleGUIQt folder.

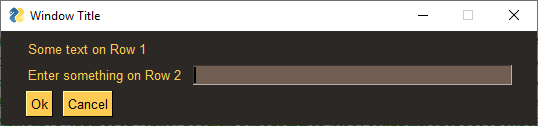

Jump Start! Get the Demo Programs & Demo Browser Quickly!

The over 300 Demo Programs will give you a jump-start and provide many design patterns for you to learn how to use PySimpleGUI and how to integrate PySimpleGUI with other packages. By far the best way to experience these demos is using the Demo Browser. This tool enables you to search, edit and run the Demo Programs.

The psgdemos PyPI Package

In Jan 2022 a new package was added so that you can get both the Demo Programs and the Demo Browser by entering 1 install command.

To get them installed quickly along with the Demo Browser, use pip to install psgdemos:

python -m pip install psgdemos

or if you're in Linux, Mac, etc, that uses python3 instead of python to launch Python:

python3 -m pip install psgdemos

Once installed, launch the demo browser by typing psgdemos from the command line"

psgdemos

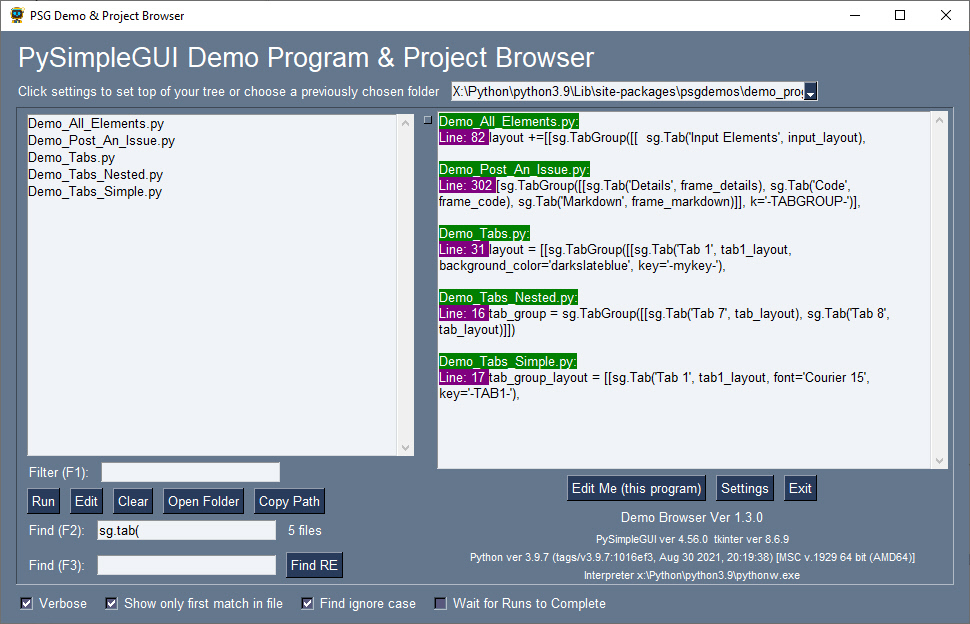

The Quick Tour

Let's take a super-brief tour around PySimpleGUI before digging into the details. There are 2 levels of windowing support in PySimpleGUI - High Level and Customized.

The high-level calls are those that perform a lot of work for you. These are not custom made windows (those are the other way of interacting with PySimpleGUI).

Let's use one of these high level calls, the popup and use it to create our first window, the obligatory "Hello World". It's a single line of code. You can use these calls like print statements, adding as many parameters and types as you desire.

import FreeSimpleGUI as sg

sg.popup('Hello From PySimpleGUI!', 'This is the shortest GUI program ever!')

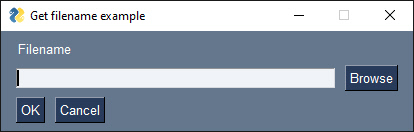

Or how about a custom GUI in 1 line of code? No kidding this is a valid program and it uses Elements and produce the same Widgets like you normally would in a tkinter program. It's just been compacted together is all, strictly for demonstration purposes as there's no need to go that extreme in compactness, unless you have a reason to and then you can be thankful it's possible to do.

import FreeSimpleGUI as sg

event, values = sg.Window('Get filename example', [[sg.Text('Filename')], [sg.Input(), sg.FileBrowse()], [sg.OK(), sg.Cancel()] ]).read(close=True)

The Beauty of Simplicity

One day I will find the right words, and they will be simple. ― Jack Kerouac

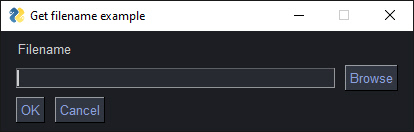

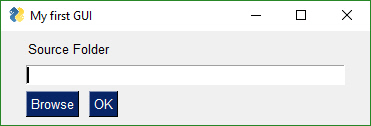

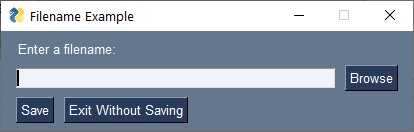

That's nice that you can crunch things into 1 line, like in the above example, but it's not readable. Let's add some whitespace so you can see the beauty of the PySimpleGUI code. And while we're at it, we'll change the color theme to something darker that's perhaps more attractive to some of you.

Take a moment and look at the code below. Can you "see" the window looking at the layout variable, knowing that each line of code represents a single row of Elements? There are 3 "rows" of Elements shown in the window and there are 3 lines of code that define it.

Creating and reading the user's inputs for the window occupy the last 2 lines of code, one to create the window, the last line shows the window to the user and gets the input values (what button they clicked, what was input in the Input Element)

import FreeSimpleGUI as sg

sg.theme('Dark Grey 13')

layout = [[sg.Text('Filename')],

[sg.Input(), sg.FileBrowse()],

[sg.OK(), sg.Cancel()]]

window = sg.Window('Get filename example', layout)

event, values = window.read()

window.close()

Unlike other GUI SDKs, you can likely understand every line of code you just read, even though you have not yet read a single instructional line from this document about how you write Elements in a layout.

There are no pesky classes you are required to write, no callback functions to worry about. None of that is required to show a window with some text, an input area and 2 buttons using PySimpleGUI.

The same code, in tkinter, is 5 times longer and I'm guessing you won't be able to just read it and understand it. While you were reading through the code, did you notice there are no comments, yet you still were able to understand, using intuition alone.

You will find this theme of Simple everywhere in and around PySimpleGUI. It's a way of thinking as well as an architecture direction. Remember, you, Mr./Ms. Developer, are at the center of the package. So, from your vantage point, of course everything should look and feel simple.

Some Examples

Polishing Your Windows = Building "Beautiful Windows"

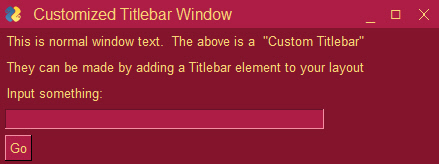

Custom Titlebars - A Trivial Start at Beautification

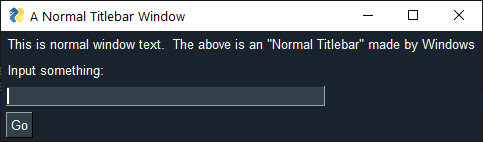

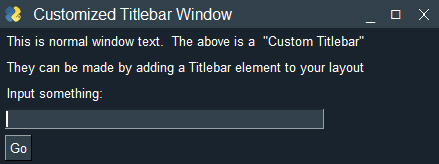

You can replace the titlebar that your operating system provides with one that is custom to your user interface by using the Titlebar element.

Normally, the Operating System provides the titlebar. This means they are unlikely to match your color scheme. Here is a Window with a dark color theme and the default titlebar provided by Windows.

It's an OK window. By adding a Titlebar element to your layout, then your window completely matches your color theme. Here is the same window with a PySimpleGUI Titlebar element

Regardless of the "Theme" you choose for your window, the Titlebar will match it.

Some Examples Of More "Polished" Windows

A note from the "2022 Mike"... these windows were created 2 years ago. A lot more work has been completed to enable even better windows using packages like Pillow. In other words, these are not the current "best" examples.

The User Screenshots Gallery is currently housed in Issue #10 on GitHub. GitHub does very strange pagination. The MIDDLE portion of the text and images on the page is hidden and you have to repeatedly press a "Load More" link.

Some of these have been "polished", others like the Matplotlib example is more a functional example to show you it works.

This chess program is capable of running multiple AI chess engines and was written by another user using PySimpleGUI.

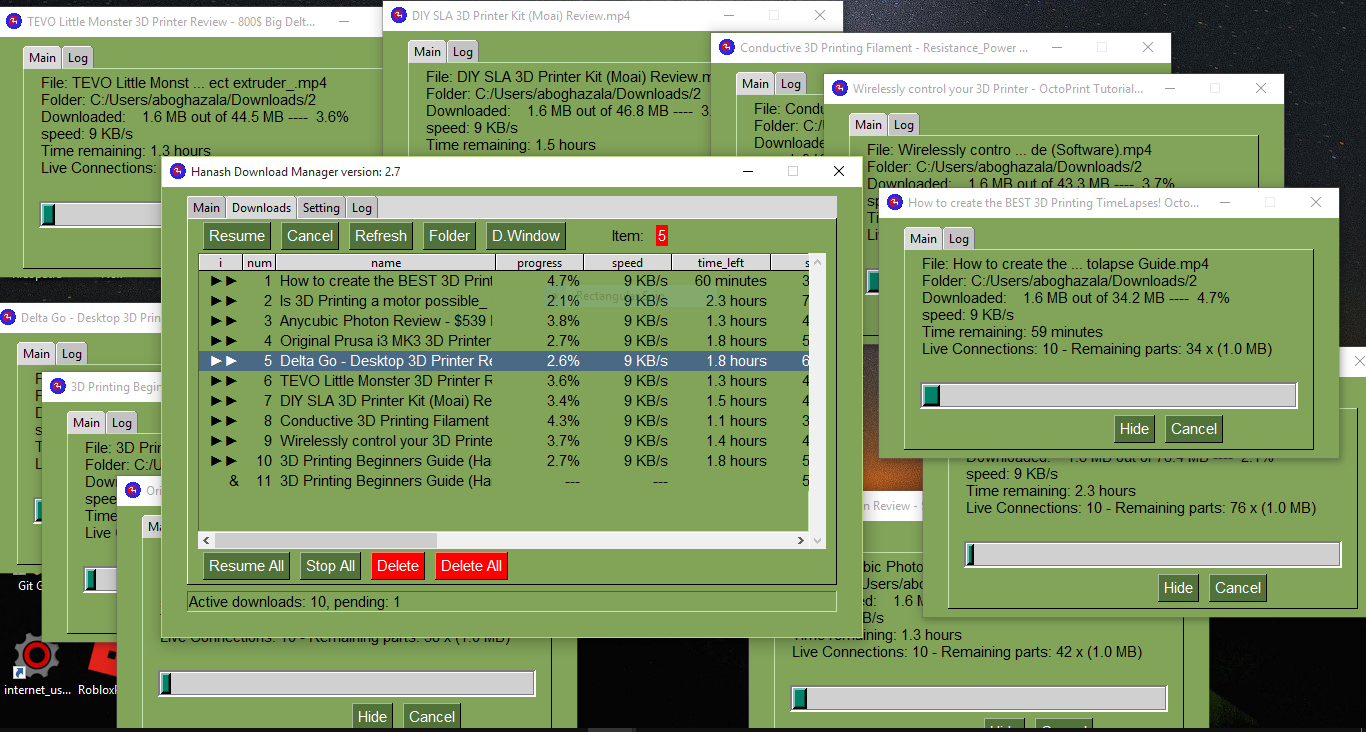

This downloader can download files as well as YouTube videos and metadata. If you're worried about multiple windows working, don't. Worried your project is "too much" or "too complex" for PySimpleGUI? Do an initial assessment if you want. Check out what others have done.

Your program have 2 or 3 windows and you're concerned? Below you'll see 11 windows open, each running independently with multiple tabs per window and progress meters that are all being updated concurrently.

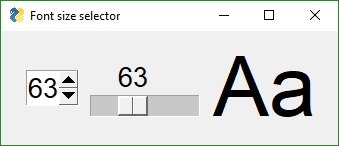

Just because you can't match a pair of socks doesn't mean your windows have to all look the same gray color. Choose from over 100 different "Themes". Add 1 line call to theme to instantly transform your window from gray to something more visually pleasing to interact with. If you misspell the theme name badly or specify a theme name is is missing from the table of allowed names, then a theme will be randomly assigned for you. Who knows, maybe the theme chosen you'll like and want to use instead of your original plan.

In PySimpleGUI release 4.6 the number of themes was dramatically increased from a couple dozen to over 100. To use the color schemes shown in the window below, add a call to theme('Theme Name) to your code, passing in the name of the desired color theme. To see this window and the list of available themes on your release of software, call the function theme_previewer(). This will create a window with the frames like those below. It will shows you exactly what's available in your version of PySimpleGUI.

In release 4.9 another 32 Color Themes were added... here are the current choices

Make beautiful looking, alpha-blended (partially transparent) Rainmeter-style Desktop Widgets that run in the background.

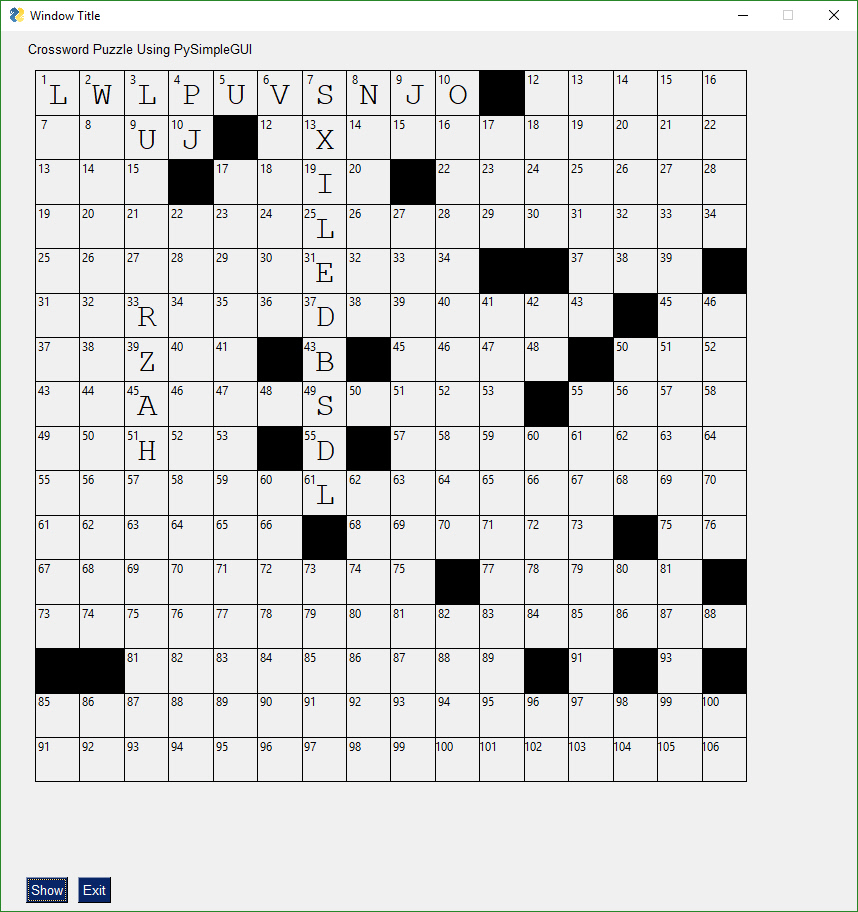

Want to build a Crossword Puzzle? No problem, the drawing primitives are there for you.

There are built-in drawing primitives

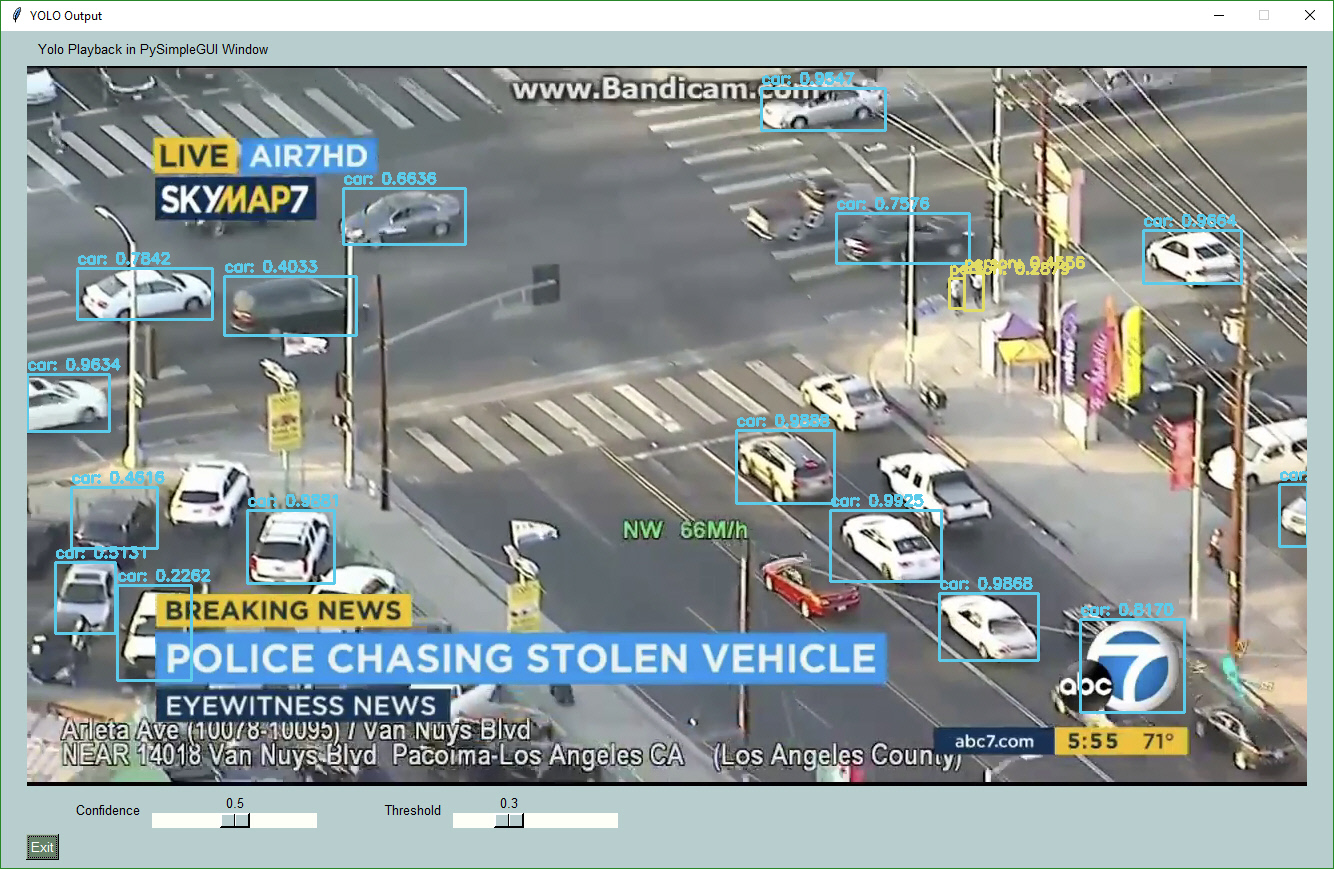

Frame from integration with a YOLO Machine Learning program that does object identification in realtime while allowing the user to adjust the algorithms settings using the sliders under the image. This level of interactivity with an AI algorithm is still unusual to find due to difficulty of merging the technologies of AI and GUI. It's no longer difficult. This program is under 200 lines of code.

Pi Windows

Perhaps you're looking for a way to interact with your Raspberry Pi in a more friendly way. Your PySimpleGUI code will run on a Pi with no problem. Tkinter is alive and well on the Pi platform. Here is a selection of some of the Elements shown on the Pi. You get the same Elements on the Pi as you do Windows and Linux.

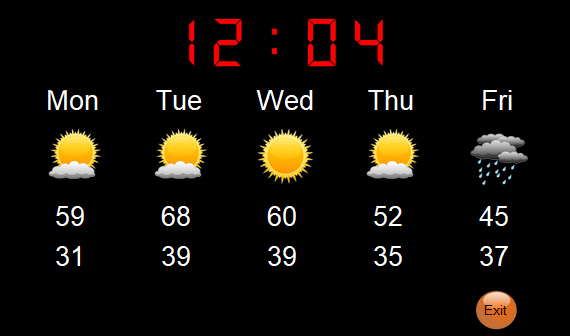

You can add custom artwork to make it look nice, like the Demo Program - Weather Forecast shown in this image:

One thing to be aware of with Pi Windows, you cannot make them semi-transparent. This means that the Window.Disappear method will not work. Your window will not disappear. Setting the Alpha Channel will have no effect.

Don't forget that you can use custom artwork anywhere, including on the Pi. The weather application looks beautiful on the Pi. Notice there are no buttons or any of the normal looking Elements visible. It's possible to build nice looking applications, even on the lower-end platforms.

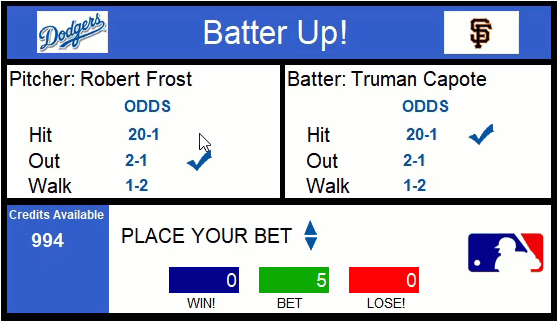

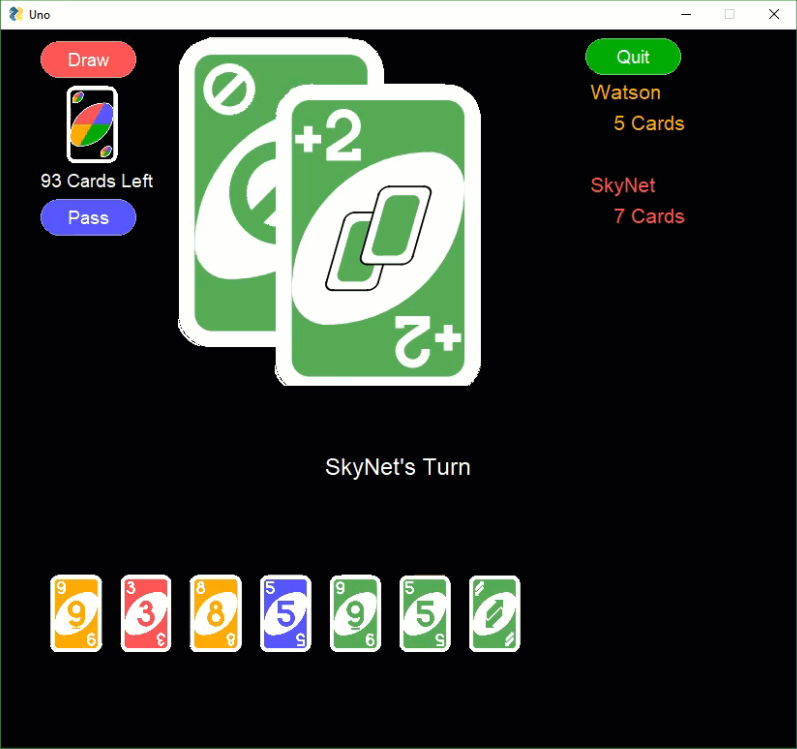

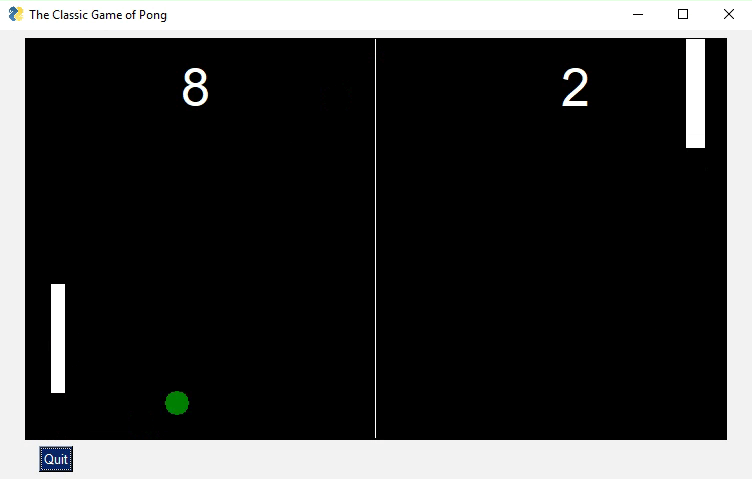

Games

It's possible to create some cool games by simply using the built-in PySimpleGUI graphic primitives' like those used in this game of pong. PyGame can also be embedded into a PySimpleGUI window and code is provided to you demonstrating how. There is also a demonstration of using the pymunk physics package that can also be used for games.

Games haven't not been explored much, yet, using PySimpleGUI.

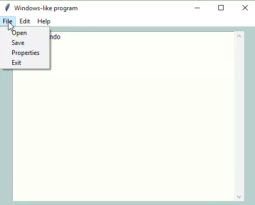

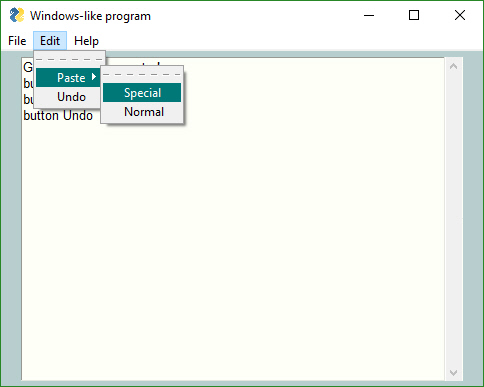

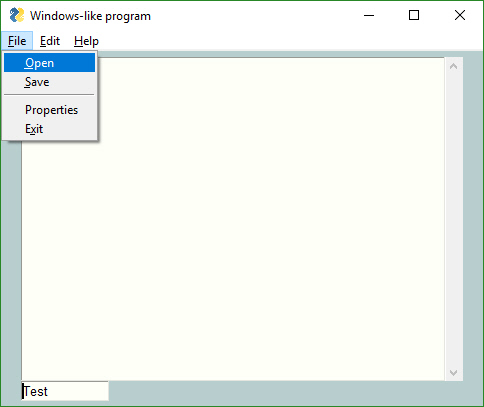

Windows Programs That Look Like Windows Programs

Do you have the desire to share your code with other people in your department, or with friends and family? Many of them may not have Python on their computer. And in the corporate environment, it may not be possible for you to install Python on their computer.

PySimpleGUI + PyInstaller to the rescue!!

Combining PySimpleGUI with PyInstaller creates something truly remarkable and special, a Python program that looks like a Windows WinForms application.

The application you see below with a working menu was created in 20 lines of Python code. It is a single .EXE file that launches straight into the screen you see. And more good news, the only icon you see on the taskbar is the window itself... there is no pesky shell window. Nice, huh?

With a simple GUI, it becomes practical to "associate" .py files with the python interpreter on Windows. Double click a py file and up pops a GUI window, a more pleasant experience than opening a dos Window and typing a command line.

There is even a PySimpleGUI program that will take your PySimpleGUI program and turn it into an EXE. It's nice because you can use a GUI to select your file and all of the output is shown in the program's window, in realtime.

The Non-OO and Non-Event-Driven Model

The two "advanced concepts" that beginning Python students have with GUIs are the use of classes and callbacks with their associated communication and coordination mechanisms (semaphores, queues, etc)

How do you make a GUI interface easy enough for first WEEK Python students?

This meant classes could be used to build and use it, but classes can not be part of the code the user writes. Of course, an OO design is quite possible to use with PySimpleGUI, but it's not a requirement. The sample code and docs stay away from writing new classes in the user space for the most part.

What about those pesky callbacks? They're difficult for beginners to grasp and they're a bit of a pain in the ass to deal with. The way PySimpleGUI got around events was to utilize a "message passing" architecture instead.

Instead of a user function being called when there's some event, instead the information is "passed" to the user when they call the function Window.read()

Everything is returned through this Window.read call. Of course the underlying GUI frameworks still perform callbacks, but they all happen inside of PySimpleGUI where they are turned into messages to pass to you.

All of the boilerplate code, the event handling, widget creation, frames containing widgets, etc, are exactly the same objects and calls that you would be writing if you wrote directly in tkinter, Qt, etc. With all of this code out of the way and done for you, that leaves you with the task of doing something useful with the information the user entered. THAT, after all, is the goal here.... getting user information and acting on it.

The full complement of Widgets are available to you via PySimpleGUI Elements. And those widgets are presented to you in a unique and fun way.

If you wish to learn more about the Architecture of PySimpleGUI, take a look at the Architecture document located on ReadTheDocs.

The Result

A GUI that's appealing to a broad audience that is highly customizable, easy to program, and is solid with few bugs and rarely crashes (99% of the time it's some other error that causes a crash).

PySimpleGUI is becoming more and more popular. The number of installs and the number of successes grows daily. Pip installs have exceeded 350,000 in the first year of existence. Over 300 people a day visit the GitHub and the project has 1,800 stars (thank you awesome users!)

The number of ports is up to 4. The number of integrations with other technologies is constantly being expanded. It's a great time to try PySimpleGUI! You've got no more than 5 or 10 minutes to lose.

Caution is needed, however, when working with the unfinished ports. PySimpleGUI, the tkinter version, is the only fully complete port. Qt is next. All of its Elements are completed, but not all of the options of each element are done. PySimpleGUIWeb is next in order of completeness and then finally PySimpleGUIWx.

Features

While simple to use, PySimpleGUI has significant depth to be explored by more advanced programmers. The feature set goes way beyond the requirements of a beginner programmer, and into the required features needed for complex multi-windowed GUIs.

The SIMPLE part of PySimpleGUI is how much effort you expend to write a GUI, not the complexity of the program you are able to create. It's literally "simple" to do... and it is not limited to simple problems.

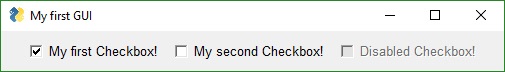

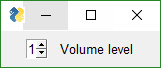

Features of PySimpleGUI include:

- Support for Python versions 2.7 and 3

- Text

- Single Line Input

- Buttons including these types:

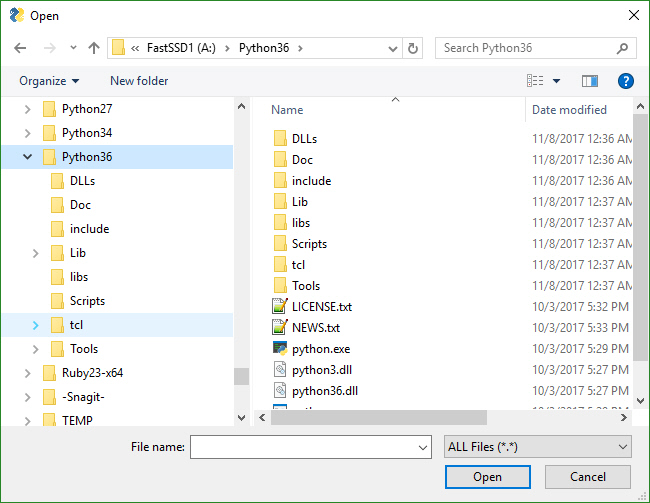

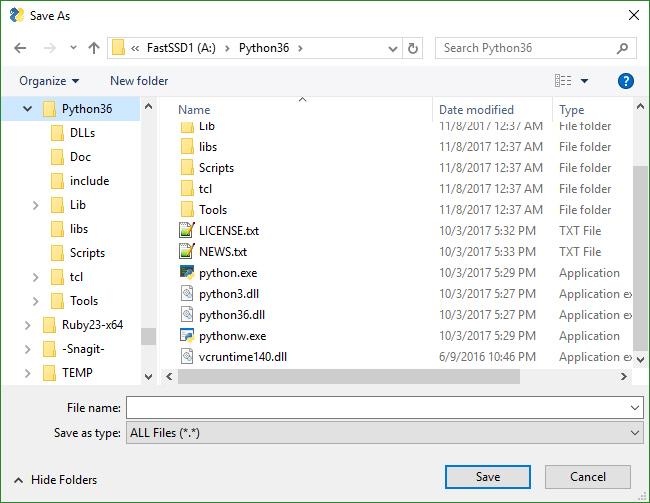

- File Browse

- Files Browse

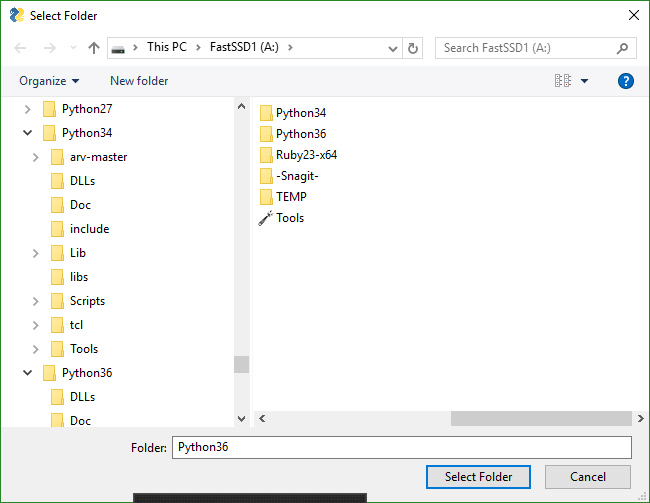

- Folder Browse

- SaveAs

- Normal button that returns event

- Close window

- Realtime

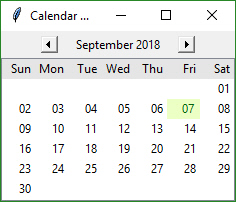

- Calendar chooser

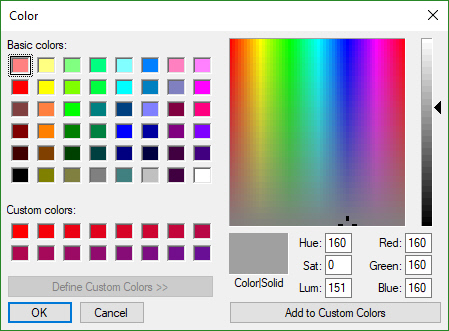

- Color chooser

- Button Menu

- TTK Buttons or "normal" TK Buttons

- Checkboxes

- Radio Buttons

- Listbox

- Option Menu

- Menubar

- Button Menu

- Slider

- Spinner

- Dial

- Graph

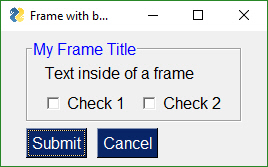

- Frame with title

- Icons

- Multi-line Text Input

- Scroll-able Output

- Images

- Tables

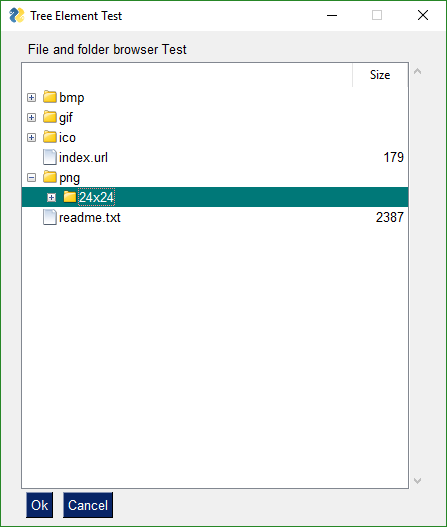

- Trees

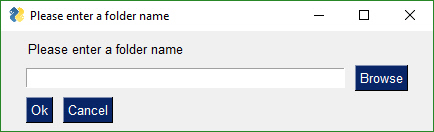

- Progress Bar Async/Non-Blocking Windows

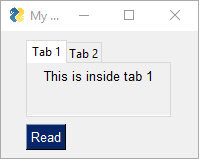

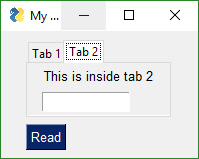

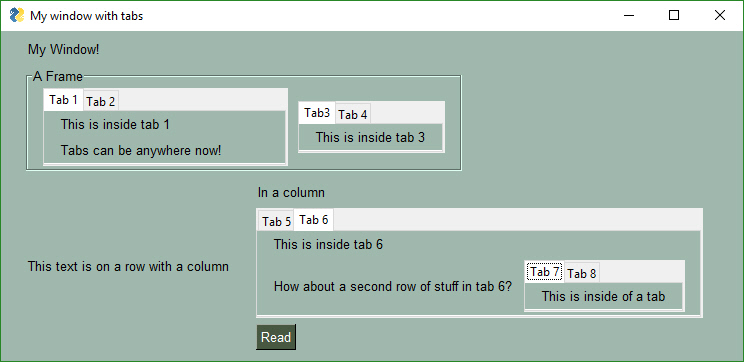

- Tabbed windows

- Paned windows

- Persistent Windows

- Multiple Windows - Unlimited number of windows can be open at the same time

- Redirect Python Output/Errors to scrolling window

- 'Higher level' APIs (e.g. MessageBox, YesNobox, ...)

- Single-Line-Of-Code Progress Bar & Debug Print

- Complete control of colors, look and feel

- Selection of pre-defined palettes

- Button images

- Horizontal and Vertical Separators

- Return values as dictionary

- Set focus

- Bind return key to buttons

- Group widgets into a column and place into window anywhere

- Scrollable columns

- Keyboard low-level key capture

- Mouse scroll-wheel support

- Get Listbox values as they are selected

- Get slider, spinner, combo as they are changed

- Update elements in a live window

- Bulk window-fill operation

- Save / Load window to/from disk

- Borderless (no titlebar) windows (very classy looking)

- Always on top windows

- Menus with ALT-hotkey

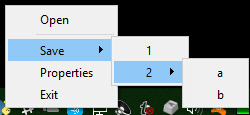

- Right click pop-up menu

- Tooltips

- Clickable text

- Transparent windows

- Movable windows

- Animated GIFs

- No async programming required (no callbacks to worry about)

- Built-in debugger and REPL

- User expandable by accessing underlying GUI Framework widgets directly

- Exec APIs - wrapper for subprocessing and threading

- UserSettings APIs - wrapper for JSON and INI files

Design Goals

With the developer being the focus, the center of it all, it was important to keep this mindset at all times, including now, today. Why is this such a big deal? Because this package was written so that the universe of Python applications can grow and can include EVERYONE into the GUI tent.

Up in 5 minutes

Success #1 has to happen immediately. Installing and then running your first GUI program. FIVE minutes is the target. The Pip install is under 1 minute. Depending on your IDE and development environment, running your first piece of code could be a copy, paste, and run. This isn't a joke target; it's for real serious.

Beginners and Advanced Together

Design an interface that both the complete beginner can understand and use that has enough depth that an advanced programmer can make some very nice looking GUIs amd not feel like they're playing with a "toy".

Success After Success

Success after success.... this is the model that will win developer's hearts. This is what users love about PySimpleGUI. Make your development progress in a way you can run and test your code often. Add a little bit, run it, see it on your screen, smile, move on.

Copy, Paste, Run.

The Cookbook and Demo Programs are there to fulfill this goal. First get the user seeing on their screen a working GUI that's similar in some way to what they want to create.

If you're wanting to play with OpenCV download the OpenCV Demo Programs and give them a try. Seeing your webcam running in the middle of a GUI window is quite a thrill if you're trying to integrate with the OpenCV package.

"Poof" instant running OpenCV based application == Happy Developer

Make Simpler Than Expected Interfaces

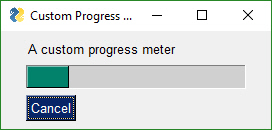

The Single Line Progress Meter is a good example. It requires one and only 1 line of code. Printing to a debug window is as easy as replacing print with sg.Print which will route your console output to a scrolling debug window.

Be Pythonic

Be Pythonic...

This one is difficult for me to define. The code implementing PySimpleGUI isn't PEP8 compliant, but it is consistent. The important thing was what the user saw and experienced while coding, NOT the choices for naming conventions in the implementation code. The user interface to FreeSimpleGUI now has a PEP8 compliant interface. The methods are snake_case now (in addition to retaining the older CamelCase names)

I ended up defining it as - attempt to use language constructs in a natural way and to exploit some of Python's interesting features. It's Python's lists and optional parameters make PySimpleGUI work smoothly.

Here are some Python-friendly aspects to PySimpleGUI:

- Windows are represented as Python lists of Elements

- Return values are an "event" such a button push and a list/dictionary of input values

- The SDK calls collapse down into a single line of Python code that presents a custom GUI and returns values should you want that extreme of a single-line solution

- Elements are all classes. Users interact with elements using class methods but are not required to write their own classes

- Allow keys and other identifiers be any format you want. Don't limit user to particular types needlessly.

- While some disagree with the single source file, I find the benefits greatly outweigh the negatives

Lofty Goals

Teach GUI Programming to Beginners

By and large PySimpleGUI is a "pattern based" SDK. Complete beginners can copy these standard design patterns or demo programs and modify them without necessarily understanding all of the nuts and bolts of what's happening. For example, they can modify a layout by adding elements even though they may not yet grasp the list of lists concept of layouts.

Beginners certainly can add more if event == 'my button': statements to the event loop that they copied from the same design pattern. They will not have to write classes to use this package.

Capture Budding Graphic Designers & Non-Programmers

The hope is that beginners that are interested in graphic design, and are taking a Python course, will have an easy way to express themselves, right from the start of their Python experience. Even if they're not the best programmers they will be able express themselves to show custom GUI layouts, colors and artwork with ease.

Fill the GUI Gap (Democratize GUIs)

There is a noticeable gap in the Python GUI solution. Fill that gap and who knows what will happen. At the moment, to make a traditional GUI window using tkinter, Qt, WxPython and Remi, it takes much more than a week, or a month of Python education to use these GUI packages.

They are out of reach of the beginners. Often WAY out of reach. And yet, time and time again, beginners that say they JUST STARTED with Python will ask on a Forum or Reddit for a GUI package recommendation. 9 times out of 10 Qt is recommended. (smacking head with hand). What a waste of characters. You might as well have just told them, "give up".

Is There a There?

Maybe there's no "there there". Or maybe a simple GUI API will enable Python to dominate yet another computing discipline like it has so many others. This is one attempt to find out. So far, it sure looks like there's PLENTY of demand in this area.

Getting Started with PySimpleGUI

There is a "Troubleshooting" section towards the end of this document should you run into real trouble. It goes into more detail about what you can do to help yourself.

Installing PySimpleGUI

Of course if you're installing for Qt, WxPython, Web, you'll use PySimpleGUIQt, PySimpleGUIWx, and PySimpleGUIWeb instead of straight PySimpleGUI in the instructions below. You should already have the underlying GUI Framework installed and perhaps tested. This includes tkinter, PySide2, WxPython, Remi

Installing on Python 3

pip install --upgrade PySimpleGUI

On some systems you need to run pip3. (Linux and Mac)

pip3 install --upgrade PySimpleGUI

On a Raspberry Pi, this is should work:

sudo pip3 install --upgrade pysimplegui

Some users have found that upgrading required using an extra flag on the pip --no-cache-dir.

pip install --upgrade --no-cache-dir PySimpleGUI

On some versions of Linux you will need to first install pip. Need the Chicken before you can get the Egg (get it... Egg?)

sudo apt install python3-pip

tkinter is a requirement for PySimpleGUI (the only requirement). Some OS variants, such as Ubuntu, do not some with tkinter already installed. If you get an error similar to:

ImportError: No module named tkinter

then you need to install tkinter.

For python 2.7

sudo apt-get install python-tk

For python 3

sudo apt-get install python3-tk

More information about installing tkinter can be found here: https://www.techinfected.net/2015/09/how-to-install-and-use-tkinter-in-ubuntu-debian-linux-mint.html

Installing typing module for Python 3.4 (Raspberry Pi)

In order for the docstrings to work correctly the typing module is used. In Python version 3.4 the typing module is not part of Python and must be installed separately. You'll see a warning printed on the console if this module isn't installed.

You can pip install typing just like PySimpleGUI. However it's not a requirement as PySimpleGUI will run fine without typing installed as it's only used by the docstrings.

Installing for Python 2.7

importANT FreeSimpleGUI27 will disappear from the GitHub on Dec 31, 2019. PLEASE migrate to 3.6 at least. It's not painful for most people.

pip install --upgrade PySimpleGUI27

or

pip2 install --upgrade PySimpleGUI27

You may need to also install "future" for version 2.7

pip install future

or

pip2 install future

Like above, you may have to install either pip or tkinter. To do this on Python 2.7:

sudo apt install python-pip

sudo apt install python-tkinter

Upgrading from GitHub Using PySimpleGUI

There is code in the PySimpleGUI package that upgrades your previously pip installed package to the latest version checked into GitHub.

It overwrites your PySimpleGUI.py file that you installed using pip with the currently posted version on GitHub. Using this method when you're ready to install the next version from PyPI or you want to maybe roll back to a PyPI release, you only need to run pip.

The PySimpleGUI "Test Harness"

If you call sg.main() then you'll get the test harness and can use the upgrade feature.

After you've pip installed, you can use the commands psgmain to run the test harness or psgupgrade to invoke the GitHub upgrade code.

There have been problems on some machines when psgmain and psgupgrade are used to upgrade PySimpleGUI. The upgrade is in-place so there can be file locking problems. If you have trouble using these commands, then you can also upgrade using this command:

python -m PySimpleGUI.PySimpleGUI upgrade

The "Safest" approach is to call sg.main() from your code and then click the red upgrade button.

Recovering From a Bad GitHub Release

If you run into a problem upgrading after upgrading from GitHub, you can likely use pip to uninstall, then re-install from PyPI to see if you can upgrade again from GitHub.

pip uninstall FreeSimpleGUI

pip install FreeSimpleGUI

Testing your installation and Troubleshooting

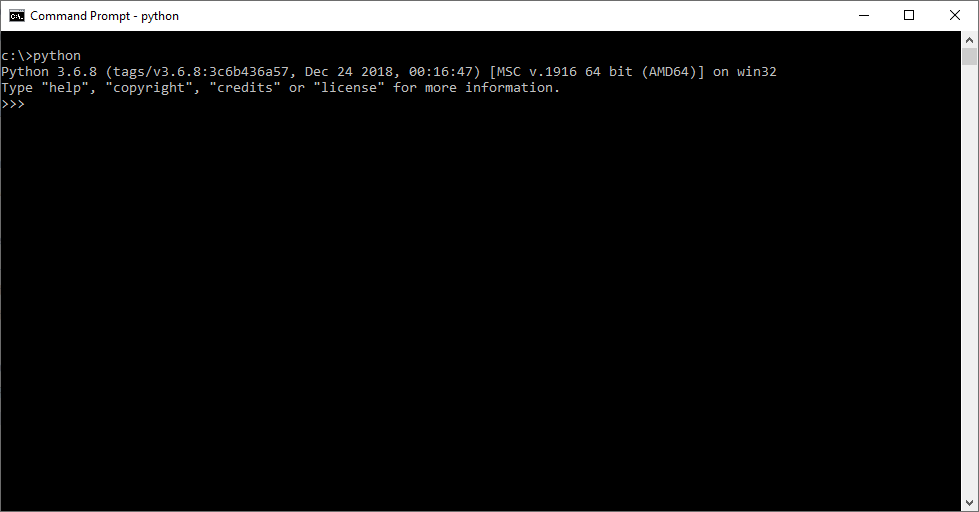

Once you have installed, or copied the .py file to your app folder, you can test the installation using python.

The Quick Test

The PySimpleGUI Test Harness pictured in the previous section on GUI upgrades is the short program that's built into PySimpleGUI that serves multiple purposes. It exercises many/most of the available Elements, displays version and location data and works as a quick self-test.

psgmain is a command you can enter to the run PySimpleGUI test harness if you pip installed. You can also use:

From your command line type:

python -m PySimpleGUI.PySimpleGUI

If you're on Linux/Mac and need to run using the command python3 then of course type that.

This will display the test harness window.

You can also test by using the REPL....

Instructions for Testing Python 2.7:

>>> import FreeSimpleGUI27

>>> PySimpleGUI27.main()

Instructions for Testing Python 3:

>>> import FreeSimpleGUI

>>> PySimpleGUI.main()

You will see a "test harness" that exercises the SDK, tells you the version number, allows you to try a number of features as well as access the built-in GitHub upgrade utility.

Finding Out Where Your PySimpleGUI Is Coming From

It's critical for you to be certain where your code is coming from and which version you're running.

Sometimes when debugging, questions arise as to exactly which PySimpleGUI you are running. The quick way to find this out is to again, run Python from the command line. This time you'll type:

>>> import FreeSimpleGUI as sg

>>> sg

When you type sg, Python will tell you the full patch to your PySimpleGUI file / package. This is critical information to know when debugging because it's really easy to forget you've got an old copy of PySimpleGUI laying around somewhere.

Finding Out Where Your PySimpleGUI Is Coming From (from within your code)

If you continue to have troubles with getting the right version of PySimpleGUI loaded, THE definitive way to determine where your program is getting PySimpleGUI from is to add a print to your program. It's that simple! You can also get the version you are running by also printing

import FreeSimpleGUI as sg

print(sg)

print(sg.version)

Just like when using the REPL >>> to determine the location, this print in your code will display the same path information.

Manual installation

If you're not connected to the net on your target machine, or pip isn't working, or you want to run the latest code from GitHub, then all you have to do is place the single PySimpleGUI source file PySimpleGUI.py (for tkinter port) in your application's folder (the folder where the py file is that imports PySimpleGUI). Your application will load that local copy of FreeSimpleGUI as if it were a package.

Be sure that you delete this PySimpleGUI.py file if you install a newer pip version. Often the sequence of events is that a bug you've reported was fixed and checked into GitHub. You download the PySimpleGUI.py file (or the appropriately named one for your port) and put with your app. Then later your fix is posted with a new release on PyPI. You'll want to delete the GitHub one before you install from pip.

Prerequisites

Python 2.7 or Python 3 tkinter

PySimpleGUI Runs on all Python3 platforms that have tkinter running on them. It has been tested on Windows, Mac, Linux, Raspberry Pi. Even runs on pypy3.

EXE file creation

If you wish to create an EXE from your PySimpleGUI application, you will need to install PyInstaller or cx_freeze. There are instructions on how to create an EXE at the bottom of this document.

The PySimpleGUI EXE Maker can be found in a repo in the PySimpleGUI GitHub account. It's a simple front-end to pyinstaller.

IDEs

A lot of people ask about IDEs, and many outright fear PyCharm. Compared to your journey of learning Python, learning to use PyCharm as your IDE is nothing. It's a DAY typically (from 1 to 8 hours). Or, if you're really really new, perhaps as much as a week to get used to. So, we're not talking about you needing to learn to flap your arms and fly.

If you found this package, then you're a bright person :-) Have some confidence in yourself for Christ sake.... I do. Not going to lead you off some cliff, promise!

Some IDEs provide virtual environments, but it's optional. PyCharm is one example. For these, you will either use their GUI interface to add packages or use their built-in terminal to do pip installs. It's not recommended for beginners to be working with Virtual Environments. They can be quite confusing. However, if you are a seasoned professional developer and know what you're doing, there is nothing about PySimpleGUI that will prevent you from working this way.

Officially Supported IDEs

A number of IDEs have known problems with PySimpleGUI. IDLE, Spyder, and Thonny all have known, demonstrable, problems with intermittent or inconsistent results, especially when a program exits and you want to continue to work with it. Any IDE that is based on tkinter is going to have issues with the straight PySimpleGUI port. This is NOT a PySimpleGUI problem.

The official list of supported IDEs is: 1. PyCharm (or course this is THE IDE to use for use with PySimpleGUI) 2. Wing 3. Visual Studio

If you're on a Raspberry Pi or some other limited environment, then you'll may have to use IDLE or Thonny. Just be aware there could be problems using the debugger to debug due to both using tkinter.

Using The Docstrings (Don't skip this section)

Beginning with the 4.0 release of PySimpleGUI, the tkinter port, a whole new world opened up for PySimpleGUI programmers, one where referencing the readme and ReadTheDocs documentation is no longer needed. PyCharm and Wing both support these docstrings REALLY well and I'm sure Visual Studio does too. Why is this important? Because it will teach you the FreeSimpleGUI SDK as you use the package.

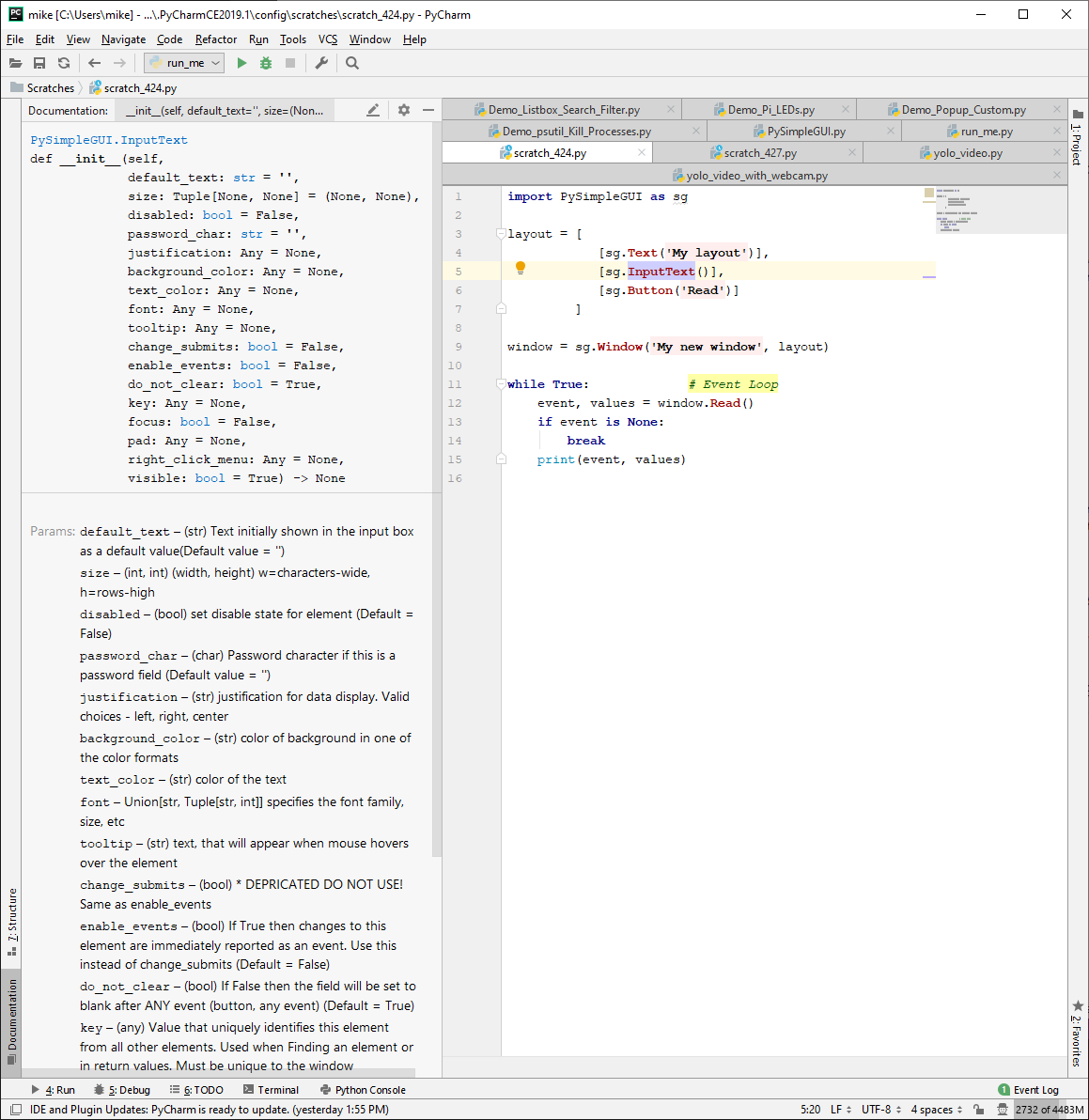

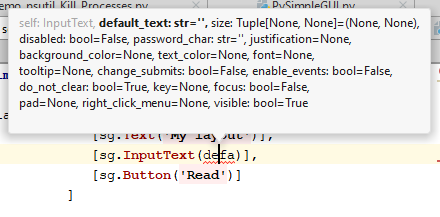

Don't know the parameters and various options for the InputText Element? It's a piece of cake with PyCharm. You can set PyCharm to automatically display documentation about the class, function, method, etc, that your cursor is currently sitting on. You can also manually bring up the documentation by pressing CONTROL+Q. When you do, you'll be treated to a window similar to this:

Note that my cursor is on InputText. On the left side of the screen, the InputText element's parameters are not just shown to you, but they are each individually described to you, and, the type is shown as well. I mean, honestly, how much more could you ask for?

OK, I suppose you could ask for a smaller window that just shows the parameters are you're typing them in. Well, OK, in PyCharm, when your cursor is between the ( ) press CONTROL+P. When you do, you'll be treated to a little window like this one:

See.... written with the "Developer" in mind, at all times. It's about YOU, Mr/Ms Developer! So enjoy your package.

The other ports of PySimpleGUI (Qt, WxPython, Web) have not yet had their docstrings updated. They're NEXT in line to be better documented. Work on a tool has already begun to make that happen sooner than later.

Type Checking With Docstrings

In version 4.17.0 a new format started being used for docstrings. This new format more clearly specified the types for each parameter. It will take some time to get all of the parameter types correctly identified and documented.

Pay attention when you're working with PyCharm and you'll see where you may have a mismatch... or where there's a bad docstring, take your pick. It will shade your code in a way that makes mismatched types very clear to see.

Using - Python 3

To use in your code, simply import....

import FreeSimpleGUI as sg

Then use either "high level" API calls or build your own windows.

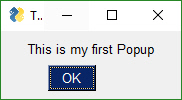

sg.popup('This is my first popup')

Yes, it's just that easy to have a window appear on the screen using Python. With PySimpleGUI, making a custom window appear isn't much more difficult. The goal is to get you running on your GUI within minutes, not hours nor days.

Python 3.7

If you must run 3.7, try 3.7.2. It does work with PySimpleGUI with no known issues.

PySimpleGUI with Python 3.7.3 and 3.7.4+. tkinter is having issues with all the newer releases. Things like Table colors stopped working entirely.

March 2020 - Still not quite sure if all issues have been ironed out with tkinter in the 3.7 and 3.8 releases.

Python 2.7

On December 31, 2019 the Python 2.7 version of PySimpleGUI will be deleted from the GitHub. Sorry but Legacy Python has no permanent home here. The security experts claim that supporting 2.7 is doing a disservice to the Python community. I understand why. There are some very narrow cases where 2.7 is required. If you have one, make a copy of PySimpleGUI27.py quickly before it disappears for good.

PEP8 Bindings For Methods and Functions

Beginning with release 4.3 of PySimpleGUI, all methods and function calls have PEP8 equivalents. This capability is only available, for the moment, on the PySimpleGUI tkinter port. It is being added, as quickly as possible, to all of the ports.

As long as you know you're sticking with tkinter for the short term, it's safe to use the new bindings.

The Non-PEP8 Methods and Functions

Why the need for these bindings? Simply put, the PySimpleGUI SDK has a PEP8 violation in the method and function names. PySimpleGUI uses CamelCase names for methods and functions. PEP8 suggests using snake_case_variables instead.

This has not caused any problems and few complaints, but it's important the the interfaces into FreeSimpleGUI be compliant. Perhaps one of the reasons for lack of complaints is that the Qt library also uses SnakeCase for its methods. This practice has the effect of labelling a package as being "not Pythonic" and also suggests that this package was originally used in another language and then ported to Python. This is exactly the situation with Qt. It was written for C++ and the interfaces continue to use C++ conventions.

PySimpleGUI was written in Python, for Python. The reason for the name problem was one of ignorance. The PEP8 convention wasn't understood by the developers when PySimpleGUI was designed and implemented.

You can, and will be able to for some time, use both names. However, at some point in the future, the CamelCase names will disappear. A utility is planned to do the conversion for the developer when the old names are remove from PySimpleGUI.

The help system will work with both names as will your IDE's docstring viewing. However, the result found will show the CamelCase names. For example help(sg.Window.read) will show the CamelCase name of the method/function. This is what will be returned:

Read(self, timeout=None, timeout_key='__TIMEOUT__', close=False)

The Renaming Convention

To convert a CamelCase method/function name to snake_case, you simply place an _ where the Upper Case letter is located. If there are none, then only the first letter is changed.

Window.FindElement becomes Window.find_element

Class Variables

For the time being, class variables will remain the way they are currently. It is unusual, in PySimpleGUI, for class variables to be modified or read by the user code so the impact of leaving them is rarely seen in your code.

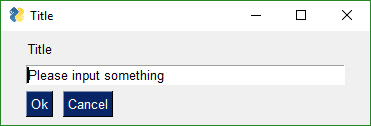

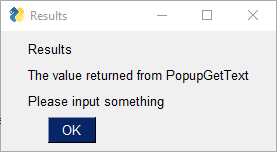

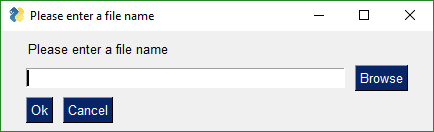

High Level API Calls - Popup's

"High level calls" are those that start with "popup". They are the most basic form of communications with the user. They are named after the type of window they create, a pop-up window. These windows are meant to be short lived while, either delivering information or collecting it, and then quickly disappearing.

Think of Popups as your first windows, sorta like your first bicycle. It worked well, but was limited. It probably wasn't long before you wanted more features and it seemed too limiting for your newly found sense of adventure.

When you've reached the point with Popups that you are thinking of filing a GitHub "Enhancement Issue" to get the Popup call extended to include a new feature that you think would be helpful.... not just to you but others is what you had in mind, right? For the good of others.

Well, don't file that enhancement request. Instead, it's at THIS time that you should immediately turn to the section entitled "Custom Window API Calls - Your First Window". Congratulations, you just graduated and are now an official "GUI Designer". Oh, never mind that you only started learning Python 2 weeks ago, you're a real GUI Designer now so buck up and start acting like one. Write a popup function of your own. And then, compact that function down to a single line of code. Yes, these popups can be written in 1 line of code. The secret is to use the close parameter on your call to window.read()

But, for now, let's stick with these 1-line window calls, the Popups. This is the list of popup calls available to you:

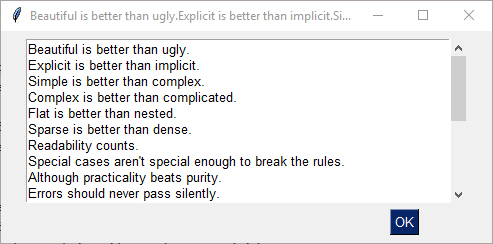

popup_animated popup_annoying popup_auto_close popup_cancel popup_error popup_get_file popup_get_folder popup_get_text popup_no_border popup_no_buttons popup_no_frame popup_no_titlebar popup_no_wait popup_notify popup_non_blocking popup_ok popup_ok_cancel popup_quick popup_quick_message popup_scrolled popup_timed popup_yes_no

Popup Output

Think of the popup call as the GUI equivalent of a print statement. It's your way of displaying results to a user in the windowed world. Each call to Popup will create a new Popup window.

popup calls are normally blocking. your program will stop executing until the user has closed the Popup window. A non-blocking window of Popup discussed in the async section.

Just like a print statement, you can pass any number of arguments you wish. They will all be turned into strings and displayed in the popup window.

There are a number of Popup output calls, each with a slightly different look or functionality (e.g. different button labels, window options).

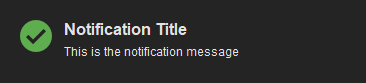

The list of Popup output functions are: - popup - popup_ok - popup_yes_no - popup_cancel - popup_ok_cancel - popup_error - popup_timed, popup_auto_close, popup_quick, popup_quick_message - popup_no_waitWait, popup_non_blocking - popup_notify

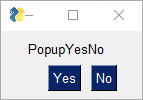

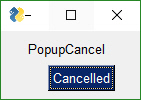

The trailing portion of the function name after Popup indicates what buttons are shown. PopupYesNo shows a pair of button with Yes and No on them. PopupCancel has a Cancel button, etc..

While these are "output" windows, they do collect input in the form of buttons. The Popup functions return the button that was clicked. If the Ok button was clicked, then Popup returns the string 'Ok'. If the user clicked the X button to close the window, then the button value returned is None or WIN_CLOSED is more explicit way of writing it.

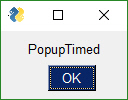

The function popup_timed or popup_auto_close are popup windows that will automatically close after come period of time.

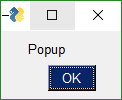

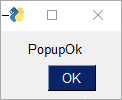

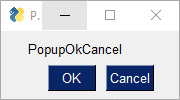

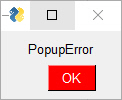

Here is a quick-reference showing how the Popup calls look.

sg.popup('popup') # Shows OK button

sg.popup_ok('popup_ok') # Shows OK button

sg.popup_yes_no('popup_yes_no') # Shows Yes and No buttons

sg.popup_cancel('popup_cancel') # Shows Cancelled button

sg.popup_ok_cancel('popup_ok_cancel') # Shows OK and Cancel buttons

sg.popup_error('popup_error') # Shows red error button

sg.popup_timed('popup_timed') # Automatically closes

sg.popup_auto_close('popup_auto_close') # Same as PopupTimed

Preview of popups:

Popup - Display a popup Window with as many parms as you wish to include. This is the GUI equivalent of the "print" statement. It's also great for "pausing" your program's flow until the user can read some error messages.

If this popup doesn't have the features you want, then you can easily make your own. Popups can be accomplished in 1 line of code: choice, _ = sg.Window('Continue?', [[sg.T('Do you want to continue?')], [sg.Yes(s=10), sg.No(s=10)]], disable_close=True).read(close=True)

popup(args=*<1 or N object>,

title = None,

button_color = None,

background_color = None,

text_color = None,

button_type = 0,

auto_close = False,

auto_close_duration = None,

custom_text = (None, None),

non_blocking = False,

icon = None,

line_width = None,

font = None,

no_titlebar = False,

grab_anywhere = False,

keep_on_top = None,

location = (None, None),

relative_location = (None, None),

any_key_closes = False,

image = None,

modal = True,

button_justification = None,

drop_whitespace = True)

Parameter Descriptions:

| Type | Name | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Any | *args | Variable number of your arguments. Load up the call with stuff to see! |

| str | title | Optional title for the window. If none provided, the first arg will be used instead. |

| (str, str) or str | button_color | Color of the buttons shown (text color, button color) |

| str | background_color | Window's background color |

| str | text_color | text color |

| int | button_type | NOT USER SET! Determines which pre-defined buttons will be shown (Default value = POPUP_BUTTONS_OK). There are many Popup functions and they call Popup, changing this parameter to get the desired effect. |

| bool | auto_close | If True the window will automatically close |

| int | auto_close_duration | time in seconds to keep window open before closing it automatically |

| (str, str) or str | custom_text | A string or pair of strings that contain the text to display on the buttons |

| bool | non_blocking | If True then will immediately return from the function without waiting for the user's input. |